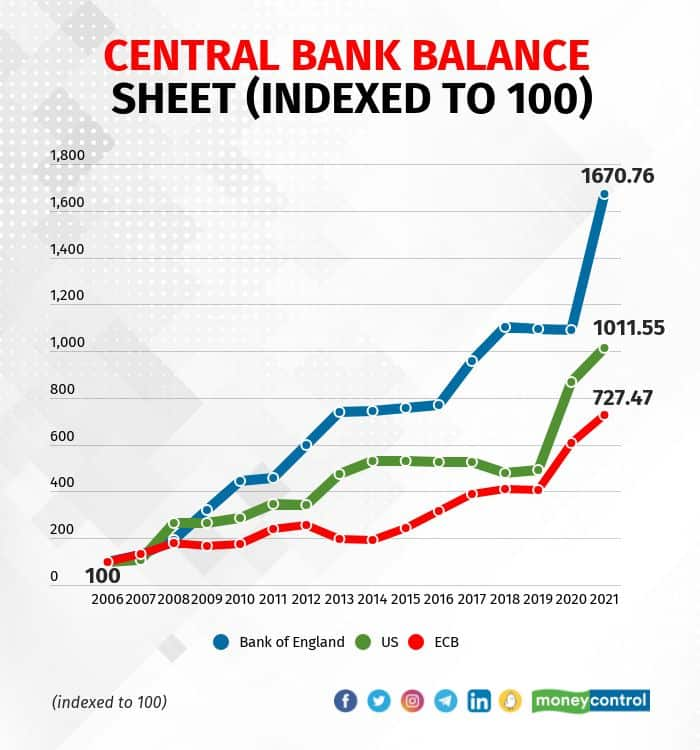

The 2008 crisis led central banks on a path not seen before in the history of monetary policy. This was particularly true for advanced countries where policy rates not just touched near zero levels but balance sheets also rose manifold. As central banks were trying to undo these policies, the pandemic struck. Again, central banks were forced to not just cut policy rates again but also expand their balance sheets significantly, as can be seen from the graph.

As the pandemic is starting to ease, and inflation appears to be more than transitory, the pressure is back on central banks to think about rolling back their ultra-easy monetary policies. One big central bank expected to reverse its policy stance was the Bank of England. In the Monetary Policy Committee meeting held recently (November 4), the markets expected the central bank to increase policy rates. The UK economy was recovering post pandemic and inflation was higher than target of 2 percent. However, the second oldest central bank not just voted to keep policy rates unchanged at 0.1 percent but also continued to expand balance sheet by buying assets. The yields of the UK 10-year sovereign bond had risen from a low of 0.5 percent in August 2021 to around 1.05 percent before the November policy. Post-policy, the yields dropped to 0.82 percent.

We have seen other major central banks such as the US Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank also showing reluctance to reverse their policy stance despite rising inflation. The officials of these central banks have treated rising inflation as transitory. Having said that, we have seen some central banks reverse policy stance. The Central Bank of Norway has raised policy rates whereas New Zealand has halted expansion of its balance sheet.

What does this mean for India and the Reserve Bank of India (RBI)?

The RBI followed the book of global central banks during the pandemic. It lowered the policy repo rate from a pre-pandemic level of 5.15 percent to 4 percent during the pandemic. The central bank also ushered in multiple policies to ease liquidity conditions and as a result its balance sheet also expanded significantly. We can see that in terms of scale, RBI’s balance sheet has expanded more than that of the ECB and is just lower than that of Federal Reserve.

Like advanced economies, inflation in India has been higher than the target 4 percent, but within the upper tolerance limit of 6 percent. In the October policy statement, the RBI has projected annual CPI inflation at 5.3 percent for 2021-22 and quarterly inflation at 5.1 percent for Q2, 4.5 percent for Q3; 5.8 percent for Q4 of 2021-22.

On the growth front, the RBI has kept GDP growth at 9.5 percent in 2021-22 consisting of 7.9 percent in Q2, 6.8 percent in Q3 and 6.1 percent in Q4 of 2021-22. There are indications that final growth numbers could be higher as indicated by rising GST tax collections, record festive shopping and so on. We have to see whether higher growth numbers will also lead to higher inflation.

Like advanced country central banks, the RBI has been ignoring calls to unwind the easy policy stance as there is uncertainty regarding the growth outlook. There is also concern that a tighter policy sooner than required will reverse the gains in economic growth. In the 6-member Monetary Policy Committee, we have seen 5 members agreeing to a continued accommodative stance with Professor JR Varma being the lone dissenter. Varma has mentioned that the pandemic has been more of a human tragedy rather an economic crisis. He opined that fiscal policy is more effective compared to monetary policy in providing relief to the impacted population. Moreover, there are signs of persistent inflation pressures than was the case earlier, which means RBI needs to act quickly by removing the accommodative stance. However, he is of the view that RBI should first raise the reverse repo rate and look to raise the repo rate over time.

Even if the RBI has chosen to keep the easy policy, the yields in bond markets have other ideas. The benchmark 10-year bond yield has increased from 6.25 percent in October 21 to near 6.4 percent recently. In the early part of the financial year, there was a tug of war between the RBI and financial markets. The latter, anticipating higher inflation and growth, bid upwards of 6 percent for 10-year bond auctions. The RBI had rejected these bids and tried to keep 10-year yields pegged to 6 percent. Eventually, the central bank started accepting the yields higher than 6 percent.

Given this background, the path to normalising monetary policy is as tricky for the RBI as for other global central banks. RBI Governor Shaktikanta Das in a recent interaction with Business Standard mentioned that normalizing monetary policy is not like rolling back a carpet. He mentioned that most of the liquidity schemes announced during the pandemic have a sunset clause and normalcy will be restored as they eventually end. He added that the RBI has been surprised by rising capital flows which has led to rise in liquidity.

Das’s three-year term was recently extended for another three years. The highlight of his first term was RBI fighting the pandemic-induced economic crisis. His second term will be marked by how RBI tackles the unwinding of its easy monetary policy. The experience with global central banks suggest this situation is a lot like Mahabharat’s chakravyuh where it is easier to get in but very difficult to get out. Will RBI be like Abhimanyu who was unable to break the chakravyuh or like Arjuna who had the knowledge to break the battle formation?

Amol Agrawal is faculty at Ahmedabad University.Views are personal and do not represent the stand of this publication.Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.