The recent bout of rupee depreciation, which has seen the currency weaken to its lowest levels against the US dollar, revives memories of the 2013 taper tantrum. In May 2013, chairman Ben Bernanke’s announcement that the US Federal Reserve will end its quantitative easing programme triggered a slide in the rupee and other emerging market currencies.

Then, India had a significantly large external financing requirement in the face of a large and growing current account deficit (CAD), along with slowing growth, fiscal stress and high inflation. The shaky macro-economic fundamentals called for a correction in the rupee. In the first half of FY2013-14, the currency lost 30 percent versus the dollar over May to August. Other countries with large external financing requirement also saw a sharp fall in their currencies.

Last year, the US Fed started reducing the size of its balance sheet, initiating tighter global liquidity conditions and squeezing risk appetite. So far, it has raised rates by 2 percentage points and remains on track for further tightening this year. This has led to an across the board strengthening of the US dollar, especially against emerging market currencies, in 2018.

The rupee too has lost almost 10 percent this year at a time when the external financing requirement is rising again. The current account deficit has widened from 0.6 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP) in FY17 to 1.9 percent in FY18 and is expected to touch 2.8 percent in FY19 on the back of a broad-based increase in non-oil, non-gold imports and rising crude oil prices. On the other hand, there have been $8.8 billion worth of portfolio outflows.

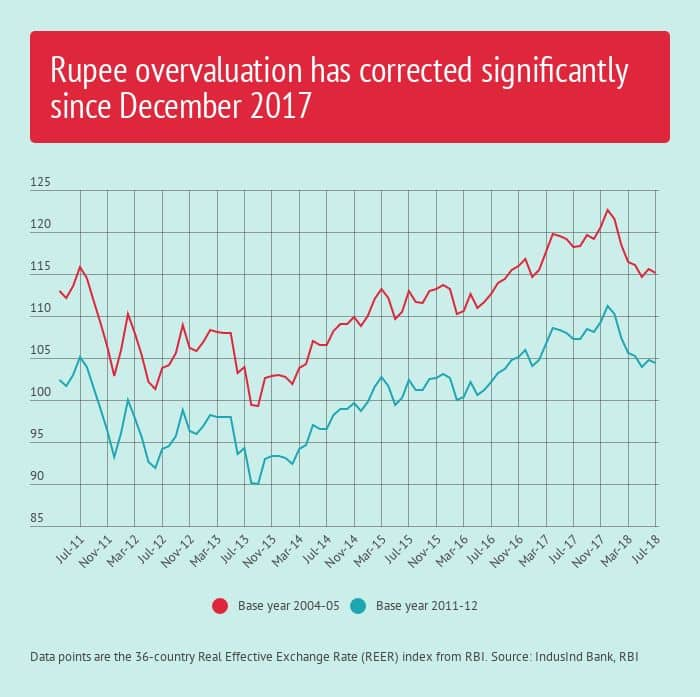

Some correction was warranted. Based on the RBI 36-country real effective exchange rate (REER) index, the rupee was overvalued by 22.6 percent in December 2017 and 15 percent in July.

That net exports have on average shaved off about 1.2 percentage points from real GDP growth over the last six quarters (till March 2018) on a widening of the trade deficit, also point towards some degree of rupee overvaluation. Hence, the move so far this year is largely in line with the fundamentals.

If the base year of the RBI REER index was adjusted to 2011-12 (same as the GDP series as against the 2004-05), the extent of overvaluation in July was only about 4.4 percent.

So, what is the appropriate policy response given that the rupee will continue facing downward pressures in the near future? Following the 2013 episode, which was far more disruptive from a macroeconomic stability perspective, Indian policymakers initiated a number of steps to safeguard the economy.

The implementation of a flexible inflation targeting for monetary policy with the consumer price index (CPI) inflation as the nominal anchor, clearly stands out. Stable inflation and inflationary expectations help in ensuring currency stability over the long run. The implementation of GST will enhance growth potential in the medium term. That along with relaxation in FDI norms will help in boosting stable foreign investment inflows.

Moreover, RBI has built sizable foreign exchange reserves since the taper tantrum taking advantage of high capital inflows and shrinking CAD. Fuel subsidies curbs, an increase in financial savings post demonetisation, and the crash in oil prices, allowed the CAD to shrink until FY17. These measures, combined with a manageable level of foreign currency debt, would help buttress the underlying strength of the rupee over medium to long term.

In the short-term, any policy response other than RBI’s intervention, would depend upon the strength of the sell-off in key emerging markets and contagion risk. The sharp depreciation of the Turkish lira in recent weeks has squeezed investor risk appetite further. The Chinese renminbi which was largely tranquil in the first half of 2018 has been under pressure too. Trade tensions with the US are escalating at a time when the Chinese policymakers are focusing on deleveraging to move away from a credit-fueled growth model followed since 2009. The renminbi has depreciated by about 5.5 percent this year. It could weaken further on monetary easing and speculative capital outflows. That is a bigger risk to Asian currencies, especially if the pace of capital outflows from China increase.

RBI has supported the rupee by selling dollars. The central bank sold $14.4 billion in the first quarter. It has also increased FII debt investment limits to get more capital inflows. The 50 bps increase in the policy rate since June, though in response to rising core CPI inflation, has helped improve the carry advantage for rupee-denominated bonds. The government, on its part, has increased custom duties on electronic items, the second largest item in India’s import basket at USD 53 billion in FY18. The possibility of fiscal slippage, however, still remains a risk.

Since a weaker rupee adds to imported inflation, the rate-setting panel might be forced to raise rates in case the pressure on the exchange rate intensifies and overwhelms softer food inflation. However, it would be mindful of raising rates sharply as that would curb growth.

In 2013, the RBI’s initial policy response was to raise rates sharply in order to curb the speculative pressures followed by the NRI swap scheme to shore up its forex reserves. The interest rate response this time can be more calibrated especially considering that rates are already moving up and forex reserves are at adequate levels. The ongoing recovery in growth is helping in restoring the growth premium for India.

In any case, a combination of higher interest rates and a weaker rupee would allow for a gradual reduction in the CAD. That is likely to happen through a reduction in non-essential imports as Indian exports are more responsive to global trade growth than the exchange rate.

In all likelihood, there is still some steam left in this bout of rupee weakness, with the broad range for now around 68-72 per US dollar. There could be some correction in case the US Fed dials down expectations of further rate increases after raising rates again in September. In the meantime, the policy steps taken since 2013 would help manage the macro-stability risks from a weaker rupee.

(The author is the chief economist of IndusInd Bank. Views are personal.)Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.