In her latest budget speech, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman announced the launch of an Urban Infrastructure Development Fund (UIDF) to be managed by the National Housing Bank for developing infrastructure in Tier-2 and Tier-3 cities. The UIDF is to be funded by banks from their shortfall under priority sector lending. While it is heartening to note the focus on Tier-2 and Tier-3 cities, three challenges need to be addressed to ensure sustainable financing that furthers climate-resilient infrastructure.

The first challenge is the quantum of investment. In the Indian context, estimates of urban infrastructure investment needs range from $500 billion to $1.2 trillion. While these numbers appear daunting, they also highlight the opportunity to innovate and explore new avenues to finance these requirements.

Funds Underutilised

The second challenge is that the existing funding is poorly utilised. In India, urban infrastructure is increasingly financed by national schemes and programmes, rather than by municipal-owned revenues. This may be an outcome of urban local bodies (ULBs) not augmenting their own revenue, and an increasing share of central and state grants in municipal finances. Municipal expenditure as a share of GDP declined from 0.82 percent in 2010-11 to 0.78 percent in 2017-18, even though there was no dearth of funds for urban infrastructure projects and there was an urgent need to improve service standards.

There was a surplus available at the pan-India level, with more than 20 percent of revenue remaining unspent by ULBs between 2010-11 and 2017-18. Poor utilisation of funds under national schemes, such as the Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation (AMRUT) and the Smart Cities Mission, has also been a matter of concern. As of December 2022, the value of projects completed under AMRUT is 42 percent (Rs 32,793 crore) of the total allocation. Under the Smart Cities Mission, as of March 2022, the value of all completed projects was only 31 percent (Rs 59,958 crore).

The third challenge is a limited pipeline of bankable projects at the city level. The underutilisation of scheme funds has often been attributed to the limited absorptive capacity of ULBs. The restrictive borrowing and exploration of public-private participation (PPP) for urban infrastructure development has also been largely due to cities’ inability to prepare a pipeline of bankable projects. This problem is further accentuated in the case of small- and medium-sized cities.

Need Innovative Financing

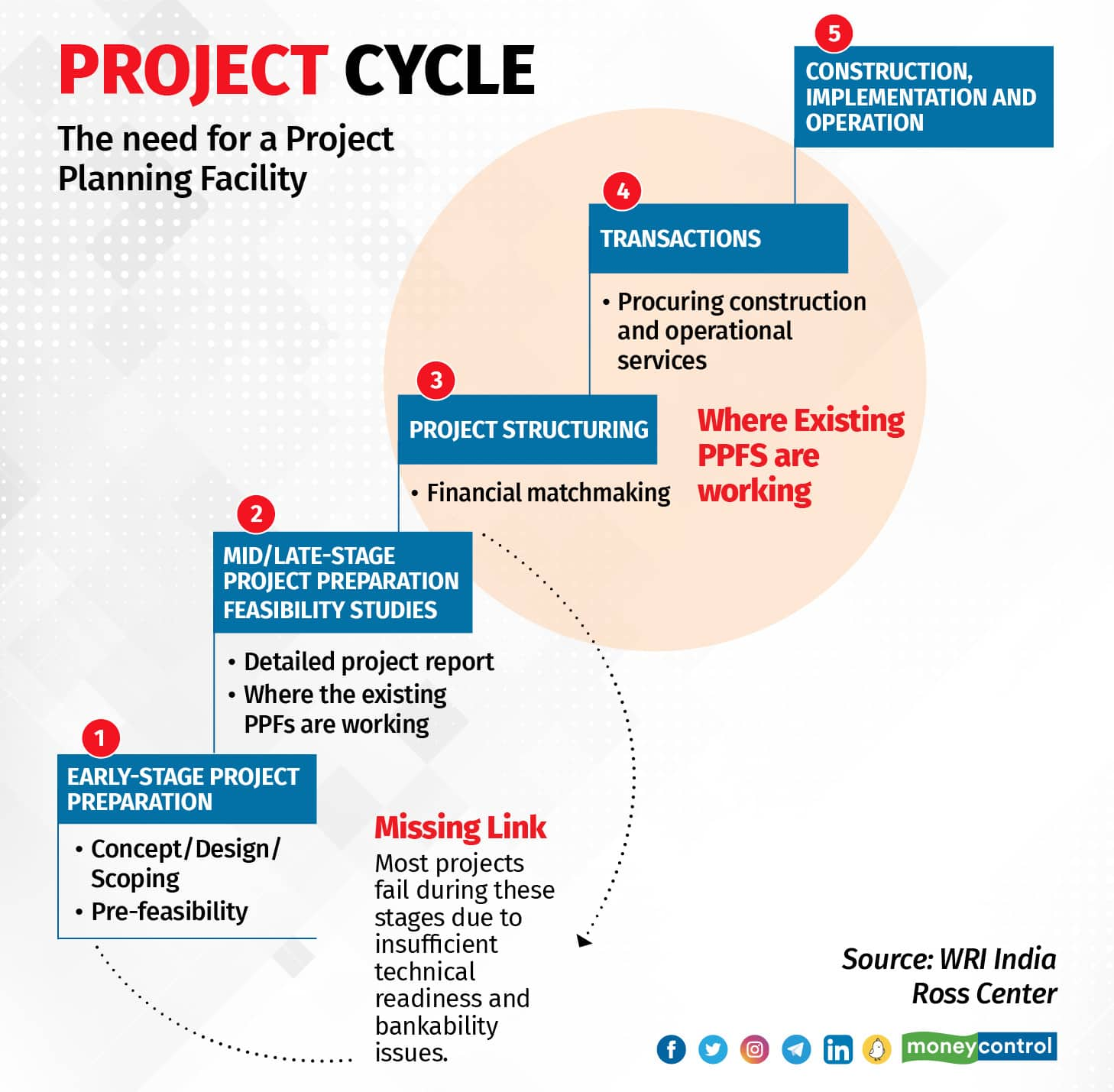

Often urban infrastructure projects cannot be financed through debt or private sector financing due to inadequate project development, the lack of a bankable project pipeline, and high costs involved during early stages of project development. Given the need for localised climate action planning, cities should consider exploring innovative public and private financing for climate-resilient infrastructure.

While banks would consider financing urban infrastructure projects through the UIDF, they would require ULBs to prepare bankable investment projects and demonstrate the capacity to execute projects in stipulated duration. While many ULBs need finance to fund infrastructure projects, they lack the capacity to prepare a capital investment plan and prioritise projects. This becomes even more challenging when cities must incorporate pressing climate, gender, and equity considerations into project design – imperative requirements that have become typical while accessing sources such as bilateral and multilateral development bank funds.

Cities would have to prepare about 250 commercially viable infrastructure projects ready for implementation if India were to meet 20 percent of its urban infrastructure funding requirement through PPP or debt. The projects must then make available detailed project reports (DPRs) that lay out the project scope, specifications, and costing, and identify action points to address associated potential environmental and social impacts. Given the significant costs involved in project preparation and the difficulty in using standardised templates in small- and medium-sized cities, it is imperative to support cities with project development efforts, to optimise for cost and efficiency.

National-level PPF

An approach that could be used to address these issues is to create a national-level Project Preparation Facility (PPF) that supports the entire value chain of a project cycle, to develop a pipeline of projects in various sectors that can attract private financing. The facility could be housed under the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (MoHUA) and facilitate Tier-2 and Tier-3 cities’ access to funds under the UIDF. Project preparation costs (pre-feasibility or feasibility studies, designs, Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) and Social Impact Assessment (SIA), and project structuring) are generally about 2-10 percent of the project cost, depending on the scale and sector. MoHUA could establish a revolving fund at the facility, under ongoing missions such as AMRUT, to fund early-stage support and project preparation, and to achieve financial closure.

The facility would need to be staffed with cross-disciplinary professionals who can help Tier-2 and Tier-3 cities in developing projects with a focus on climate resilience and gender equity, disability, and social inclusion (GEDSI) for various sectors. Additionally, various city projects, selected under national missions and schemes, could get their projects vetted through this facility. This would enable cities to explore funds available under existing missions as gap funding for projects or to enhance the financial sustainability of ongoing and upcoming projects.

In the long run, the facility would contribute to improved creditworthiness of ULBs by providing a track record of successful projects. Accessing funds, under UIDF, may also inculcate fiscal discipline and enable cities to maintain and publish disclosures at regular intervals. In addition, PPF can also help with Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning (MEL) of the projects and act as a feedback loop for improving project design and delivery based on impacts and outcomes envisaged. This track record of projects, and financial management, would be useful in informing private investors of investment opportunities in Tier-2 and Tier-3 cities, thereby creating a virtuous cycle of sustainable financing for infrastructure development.

Pavan Ankonapalli is Program Lead, Urban Development, and Jaya Dhindaw is Program Director, Integrated Urban Development, at WRI India. Views are personal, and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.