Agricultural distress and joblessness are not new issues in India, but they often hog the limelight prior to elections. This year is no different. After toying with several policies ranging from farm loan waiver to hiking minimum support prices (MSP) for farm produce and reservation for the not so well off among higher castes, the government seems to be running out of piecemeal alternatives. It now needs to do something more radical if it is serious about 'wiping every tear from every eye'.

Universal Basic Income (UBI) sounds appealing in this context. It is premised on the idea that a just society needs to guarantee each individual a minimum income, which they can count on and one provides the necessary material foundation for a life with access to basic goods and dignity.

A UBI, like many rights, is unconditional and universal – it requires that every person should have a right to basic income to cover their needs, just by virtue of being citizens. In a country like India, UBI can be pegged at a relatively low level of income but can yield decent welfare gains.

The case for Universal Basic IncomeUBI has three components: universality, unconditionality and agency. The proponents of UBI argue that poverty and vulnerability of the poor can be tackled very swiftly with this cash transfer programme. The poor in India have been treated as objects with in-kind transfers. An unconditional cash transfer treats them as agents and entrusts them the responsibility of using welfare spending as they see best.

Since all individuals are targeted, the exclusion error (the real poor being left out) is zero. The income floor provides a safety net against health, income and other shocks, and imparts psychological benefits as a guaranteed income reduces the pressure of finding basic living on a daily basis.

The payment transfer will encourage greater use of bank accounts, give beneficiaries better access to formal credit and reduce the administrative burden should it largely replace the plethora of government schemes.

Areas for concernCritics of UBI are quick to point out that a cash transfer programme will promote conspicuous spending or spending on social evils like alcohol, tobacco etc. Another argument against UBI is that it will lead to a moral hazard – free money will make people lazy and they will drop out of the labour market. In the Indian context, prevalent gender norms may regulate the sharing of such income within the household with men likely to exercise control over spending. Unlike, say food subsidies, which are not subject to fluctuating market prices, a cash transfer’s purchasing power may be severely curtailed by market fluctuations.

In addition, the idea of an equal transfer to the rich might trump the idea of state welfare for the poor. Finally, UBI may put undue pressure on India’s banking system, especially the beleaguered state-run banks.

Even if one ignores the critics and focuses on the positives, the fact remains that UBI will be a huge expense and the cash starved government may not have the financial wherewithal to take the leap.

In this context, it is important to note that as per the Union Budget of 2016-17, there were about 950 centrally sponsored sub-schemes in India, accounting for about five percent of GDP. The magnitude would be larger if states were included.

But the important question to ask is how effective are the existing programmes in alleviating poverty? Misallocation (measured by poorer areas obtaining a lower share of government resources) is evident with backward districts (accounting for 40 percent of total poor) receiving only a small share in most flagship schemes.

Source: Economic Survey

While the concept of universality reduces the burden on administration by doing away with the tedious task of separating the poor from the non-poor, UBI is neither politically astute nor fiscally prudent at this juncture.

What one could realistically expect is a truncated version of UBI with the beneficiaries being the bottom of the pyramid – the lowest 40% of the population. Going by the Economic Survey, if the UBI is pegged at an annual transfer of Rs 8,241 per annum, covering 40% of the population will cost around Rs 4.38 lakh crore, which is 2.3 percent of FY19 nominal GDP.

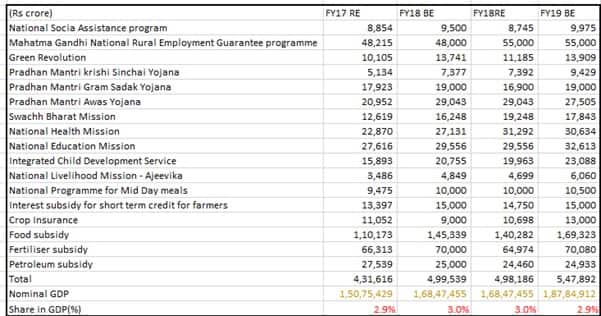

The moot question therefore is how easy or difficult is it to find the resources? If one looks at the large heads of subsidies and the flagship schemes of the government, our rough calculation suggests a broad allocation of 2.9% of GDP in FY19.

Source: India Budget

Hence, UBI even in a diluted format can only see the light of the day if the government is ready to dump all its existing schemes in favour of UBI. Will such a radical step yield a big enough political dividend to warrant such a massive overhaul?

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.