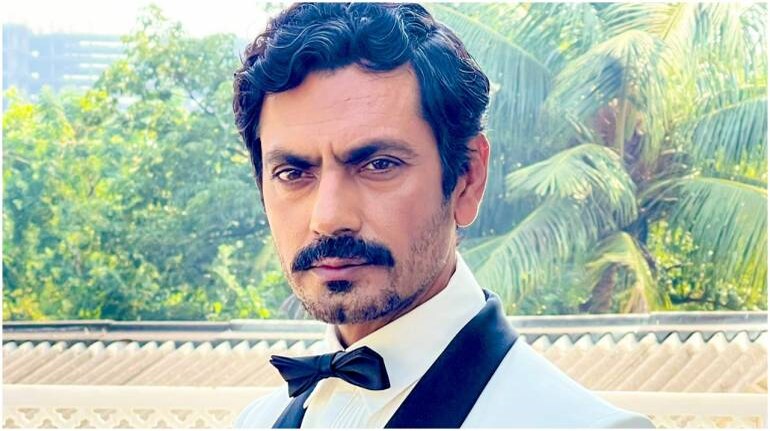

That many middle-aged Indians live in denial about the existence of anxiety and depression, in spite of the very real and damning evidence that says otherwise, is no secret. This is, perhaps, why Nawazuddin Siddiqui’s comment on depression might be surprising for some, but for GenZ and young millennials, who have often seen their parents downplay their mental-health struggles, it is proof how out-of-touch middle-aged India is with the worsening mental-health crisis. “I come from a place where, if I would tell my father that I am feeling depressed, he would give me one tight slap… Depression wahan nahi thha, kisi ko bhi nahi hota wahan depression, sab khush hai (No one gets depressed in villages, everyone is happy there). But I learnt about anxiety, depression, and bipolar after coming to the city.”

Silent epidemic raging through villagesOne wouldn’t necessarily have to whip up statistics to disprove Siddiqui’s assertions. First, he generalised his individual experience and used it to negate the presence of mental-health disorder in villages. Second, just because he hasn’t experienced depression in his village or that there aren’t enough cases that are reported, doesn’t mean rural India isn’t facing a mental-health epidemic like urban India. Still, Nawaz is just a Google search away from finding out that of the 20 per cent of the country’s population who suffer from mental illness, only 12 per cent at the most seek aid for their mental-health concerns, and those who do are more likely to be located in urban areas and ensconced in socioeconomic privilege. Add to this the poor medical infrastructure in villages and lack of connectivity, and the possibility of rural Indians seeking psychiatric treatment is negligible. There’s also a stigma around mental illnesses. If one dares to say they are not okay, there is obviously the thappad that Nawaz so proudly talks about that might come their way.

The cross-generational denialNawaz faced backlash for his comments but instead of backtracking or, at the very least, apologising to those triggered by his statement, he doubled down on his claims and said — "I was relating my experience. Maybe I am wrong. But if I go to my village, three hours from here, and say that I have depression, I will be slapped. What is depression, I will be asked." Nawaz’s complete denial to understand the nuances and complexities of mental health is seen across middle-aged Indians where they’d rather make up excuses out of thin air to explain the blatantly obvious symptoms of mental illness instead of accepting its existence and seeking help.

One possible explanation of the vehement refusal of older generations is rooted in intergenerational trauma. Parents discipline their children and use the same parenting patterns on them that they learnt from their parents. Coming from a generation where not just men but even women were discouraged from showing signs of weakness and vulnerability, accepting that they (or someone they know) has a mental illness would shake up their belief system, leading the parents to question every single thing they were taught about parenting. The process of unlearning one’s long-held beliefs can be very painful and triggering and not all middle aged Indian parents are willing to go through the process at that stage of their life.

So, when there is no explanation for the symptoms of mental illness, an explanation is invented, often out of thin air.

Laziness, black magic and victim-blamingSince superstitious beliefs are rampant in India, one often mistakes more serious ailments such as schizophrenia, psychosis and bipolar disorder for the paranormal. The examples are endless. The Delhi Burari house of horrors in one such case, which saw a seemingly ‘normal’, ‘healthy’, and ‘high functioning’ family of 11 people die by mass suicide. Everything — from Black Magic, to tantriks, astrologers, and evil spirits were blamed before the investigators finally reached the conclusion that the mass suicide was a result of shared psychosis. Down south in Karnataka, fear gripped the residents in 2013. They claimed that bhanamathi, an ancient Indian witchcraft, was leading to ill-effects in people: “loud screaming, tearing of clothes, singing songs, sudden appearance of wounds all over body”. It was only after a Government-appointed scientific committee’s investigation, that it was revealed that the ‘attacks’ were symptoms of mental illnesses which were attributed to the supernatural due to fear and ignorance.

Besides black magic, another common phenomenon seen not just in India but across the world is blaming one’s mental health problems on their physical health and food consumption. It is important to mention here that some antidepressants lead to weight gain which is likely to invite more such comments, leading to a vicious cycle. Black magic, diet, weather, earthquakes — Indians would blame mental health crisis on everything except acknowledging its presence, even if they are struggling with it themselves.

Not just Nawaz: Indians in denial about mental healthNawaz represents just one of the many middle-aged Indians who often downplay their own mental-health struggles. In an age where a ‘walk in the park’ or ‘digital detox’ are suggested as genuine treatments for anxiety disorders, there is a long way to go. In 2022, head of geriatric psychiatry at NIMHANS Dr PT Sivakumar had said that there is a lack of awareness among the elderly about the most common mental health issues of depression and dementia. He further added that family members often get angry responses from the elderly when suggesting treatment for mental health issues.

While one might get triggered by Nawaz’s comments, there is no denying that many agree with his sentiments. There is a long way to go — perhaps, years of sensitisation and normalising seeking help before one gets a hug, not a slap, when they open up about their mental illness.

If you need support or know someone who does, reach out to your nearest mental health specialist. AASRA: 91-9820466726 (24 hours)Sneha Foundation: 91-44-24640050 (24 hours) Vandrevala Foundation for Mental Health: 1860-2662-345 and 1800-2333-330 (24 hours) iCall: 9152987821 (available from Monday to Saturday, 8 am-10 pm) Connecting NGO: 18002094353 (available from 12 pm-8 pm)Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.