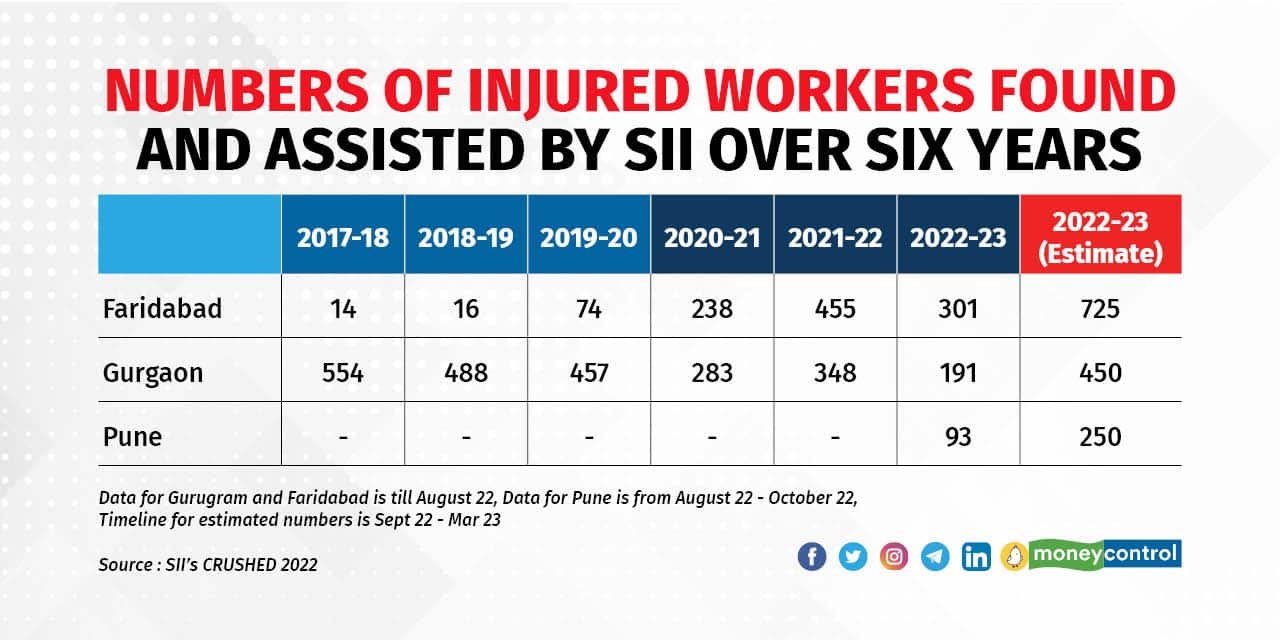

More than 585 workers in the Indian auto sector supply chain lost their hands or fingers in the auto industry hubs of Gurugram, Faridabad and Pune in the period from April 2021 to August 2022, according to a report that illustrates the dangerous working conditions in factories that employees are often exposed to.

Major automobile makers such as Maruti Suzuki, Honda, Hero MotoCorp, JCB, Mahindra, and Tata Motors accounted for more than 10 percent of these crush injuries, showed the Safe In India Foundation (SII)’s annual report Crushed 2022.

SII, a civil society organization started by three alumni of IIMA, assists workers in accessing ESIC healthcare, compensations and facilitating their ESIC claims, and also influences auto-sector to prevent accidents in their supply chain.

Top contributors to the injuries include Haryana’s Gurugram and Faridabad (Maruti-Suzuki, Hero, and Honda); Pune, Maharashtra (Tata Motors and Mahindra); Chennai, Tamil Nadu (TVS, Ashok Leyland, and Tata Motors); Karnataka (Toyota, Tata Motors, and Ashok Leyland); Rudrapur, Uttarakhand (Tata Motors, Bajaj and Mahindra) and Neemrana, Rajasthan (Honda, Maruti Suzuki and Hero).

Also Read: Why you should buy health insurance now, and not wait till retirement

The severity of injuries suffered in factory accidents in Pune appears to be worse than in Haryana. In Pune, 83 percent of workers lost a body part in an accident between April 2021-August 2022; 67 percent did so in Haryana in the same period.

A typical crush injury to fingers results in the loss of two fingers per injured worker; about 60-70 percent of injured workers still report loss of body parts, indicating continued dangerous working conditions they are exposed to in automobile factories.

The report said that a large number of injuries on machines befall helpers (76.7 percent in Pune), who, legally, should not even be operating machines.

“This happens in the auto sector despite ASDC prescribing a minimum education level of 8th standard for press shop operators, considering this a skilled job; helpers hardly ever meet this requirement,” it said. ASDC is short for Automotive Skills Development Council.

Overworked; lack of safety sensors

SII noted that 50 percent of injured employees work 12-hour shifts, 6 days a week, and are not fully reimbursed for overtime. It also alleged false reporting in official accident reports.

In a review of 80 accident reports, SII found that 31 (39 percent) stated a shift duration of 8 to 9 hours, whereas these 31 injured workers told SII they were on an over 12-hour shift at the time of suffering the injury.

More than 80 percent of injured workers from Haryana report working on machines without safety sensors at the time of the accident. Power press machines that injured them were operating without having undergone the required inspection.

Also Read: Your guide to picking the right health insurance policy

When Rahul Kumar Singh, a die-cast machine operator at a factory that makes parts for major auto brands, complained that a “limit button” of the machine he was workin on seemed to have developed a fault, his request was largely ignored.

Unfortunately, on August 22, 2022, Singh got his hand stuck in the machine. “I lost half of the index finger of my right hand. I was making rings for the oil tank of Bajaj bikes,” the SII report quoted him as saying.

A human resource executive took him to Diamond Hospital, a private facility, instead of an Employees' State Insurance Corporation (ESIC) Hospital for treatment. Singh claimed that the factory had no safeguards in place and protective equipment was provided only during safety audits. Although Honda representatives frequently visited the factory to conduct quality checks, nobody seemed to be concerned about the workers' wellbeing, the report added.

A week after receiving his fitness letter from ESIC, where he was finally taken, Singh returned to work. He was not provided any alternative work despite having a lost finger and operated the same machine. Despite his still-swollen hands, he operated the machine for 10 days and on the 11th day he was sent home permanently.

“While India’s behemoth auto sector contributes to around 7 percent of the national GDP and about half of Indian manufacturing GDP, its prosperity doesn’t appear to trickle down to millions of workers in the supply chain and indeed in their increasing proportion of contract workers. It's not without such reason that Indian labour productivity is currently ranked 128th in the world,” said Sandeep Sachdeva, co-founder and Chief Executive Officer of SII.

Under Section 7B of the India Factories Act, every person who undertakes to design or manufacture any article, may carry out or arrange for research to eliminate or minimise any risks to the health or safety of the employees engaged in the work.

SII said Haryana and Maharashtra state factory inspections have been near consistently reducing for years. In 2012, 2,720 Industrial Safety and Health department factory inspections were carried out; the number fell to just 393 in 2020.

While Maharashtra witnessed an increase in factory inspections from 11,873 in 2012 to 14,352 in 2014, it declined to just 4,598 in 2020.

Insurance woes

The Employees’ State Insurance Act 1948 encompasses certain health-related eventualities that the workers are generally exposed to such as sickness, maternity, temporary or permanent disablement, occupational disease or death due to injury, resulting in loss of wages or earning capacity.

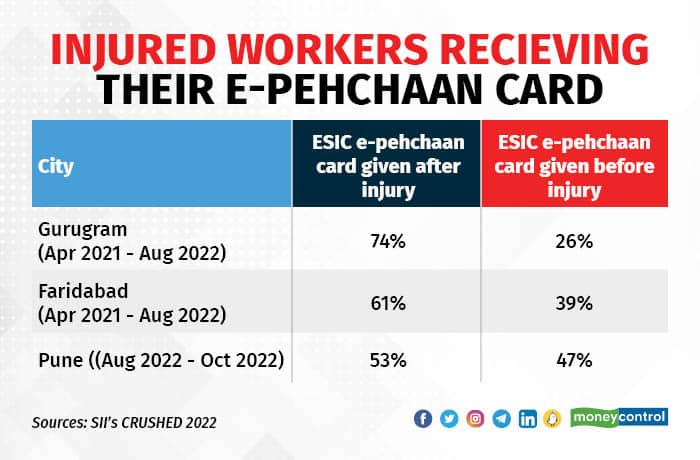

The ESIC e-Pehchaan (identity) card enables workers and their eligible dependents to access primary, secondary, and tertiary healthcare services, and compensation in case of sickness, injuries, unemployment, childbirth and death.

The report said a large majority of injured workers had not received their ESIC e-Pehchaan card on the day of joining their jobs, as the ESIC regulations require. All these injured workers did receive their cards a few days after the accident.

“In SII’s discussions, it found ESIC HQ aware of and indeed concerned about this issue and terms it as ‘Post Accident Registration’, though it does not appear to collect centralised information on this non-compliance,” the report said.

SII said it is aware of many instances where the ESIC premium deducted from workers’ compensation had not been deposited with ESIC; such workers are, therefore, not even registered with ESIC.

“Possibly as a result of this, more than half of injured workers are first taken to a private hospital, while ESIC paperwork is ‘completed’ and then taken to ESIC hospitals often after one to three days of injury,” it said in the report.

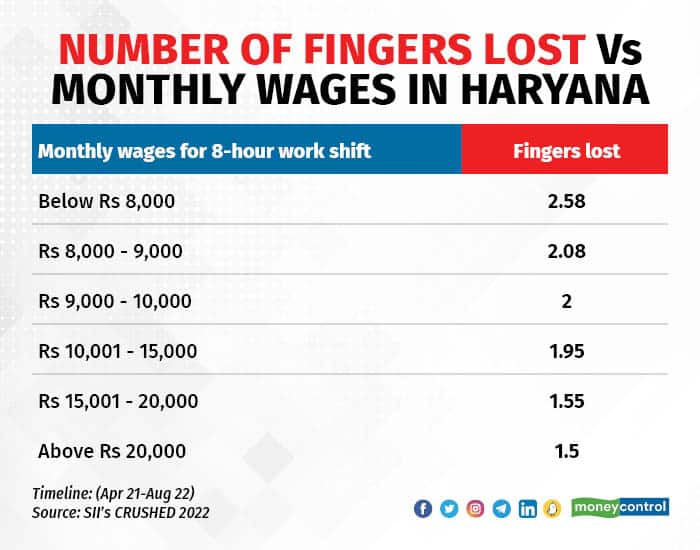

Lower the wages, worse the injury

Workers earning less than Rs 8,000/month for an 8-hour workday lost an average of 2.58 fingers in Haryana and 4.5 fingers in Pune; much worse than an average of 1.55 fingers lost in Haryana and 2 fingers lost in Pune by those earning more than Rs. 15,000.

“It may be due to helpers being asked to operate machines, as is often seen, without adequate training and/or experience,” SII said.

In Gurugram, around 6 percent of injured workers and in Faridabad, around 13 percent of injured workers appear to be paid below the minimum wages due to a skilled worker.

According to ASDC criteria, a press shop assistant/helper must have a minimum educational qualification of Class 8 and a pre-requisite licence or training in “basic press shop and housekeeping skills 5S and Safety.” The 5S refers to sort, set in order, shine, standardize and sustain.

Press shop operator at Level 4 must have a minimum educational qualification of Class 10 and pre-requisite licence or training in “press shop operations, different pressing processes used in the organisation 5S & Safety.”

In Gurugram, around 7 percent of injured workers and in Faridabad, around 25 percent of injured workers were found to not have been educated at all. SII does not collect specific data on below Class 8 separately, which is another significant proportion.

Overall, it appears that more than 81 percent of injured workers were below Class 10 and all of them were operating machines when injured in non-compliance with guidelines adopted by ASDC for the industry, the report said.

“We are encouraged by (varying) degrees of engagement and agreement on policy improvements/ actions with SIAM (Society of Indian Automobile Manufacturers), Maruti-Suzuki, Honda, Eicher, Bajaj, Tata Motors, Hero, and Hyundai. Regretfully, Ashok Leyland, Mahindra, and TVS have not yet engaged meaningfully,” Sachdeva said.

“We had 17 brands attend the first joint industry meeting chaired by SIAM. There is a long way to go for these brands individually and collectively. They also need to fund SIAM to coordinate joint actions,” he added.

Moneycontrol has sent an email to SIAM for comment and the story will be updated when a response arrives.

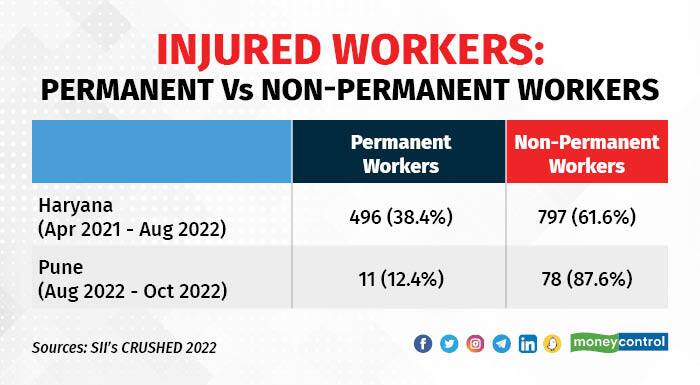

Non-permanent workers bear the brunt

In Haryana, the proportion of non-permanent injured workers continues to be high at around 62 percent (70 percent in 2021). This proportion is even higher in Pune, Maharashtra, where almost 88 percent of injured workers met and assisted by SII were in non-permanent roles.

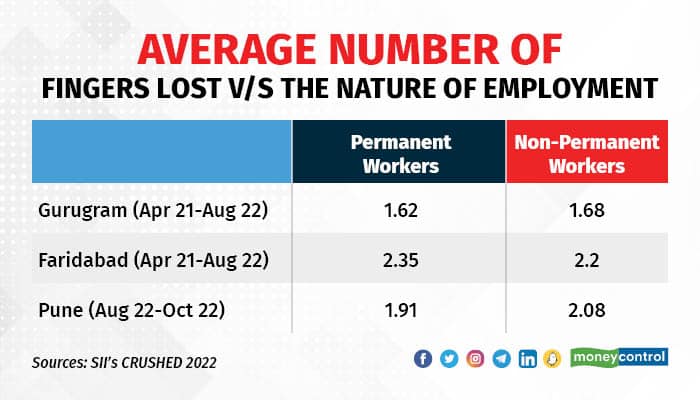

In Gurugram and Pune, the average number of fingers lost is higher for non-permanent workers. In Faridabad, the injured workers in permanent roles, on average, lose a higher number of fingers compared to the non-permanent workers.

“One of the plausible reasons identified is the change in the nature of employment from non-permanent to a permanent role after a worker meets with an accident,” the report pointed out.

The report features first-hand data from more than 6 years of SII’s operations and on over 4,000 injured workers in the auto-sector hubs in Haryana (Gurgaon and Faridabad) and more recently in Maharashtra.

It also includes data from a time-limited national survey of a few auto-sector hubs in Karnataka, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, and Uttarakhand. Both exercises covered accidents in the deeper supply chains of more than 20 national auto brands.

SII collected secondary data on worker injuries from official data sources, such as the Directorate General Factory Advice Service and Labour Institutes (DG FASLI)-which published factory accident numbers across India.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!