Two new chronicles that illuminate the life of Kekoo Gandhy, a key figure in Bombay’s (Mumbai's) art world, and his embodiment of how art, politics and society can be majestically inseparable — Kekee Manzil: House of Art, a personal documentary by Behroze Gandhy and a rigorously researched and acutely observed biography, Citizen Gallery: The Gandhys of Chemould and the Birth of Modern Art in Bombay — came out this February.

The book had a formal unveiling at the India Art Fair and is available at bookstores, and the film, made by Gandhy’s daughter Behroze, will be screened at the Pompidou Centre, Paris, on 17 February followed by another screening at the British Film Institute on 24 February.

(From left) Shireen Gandhy with parents Kekoo Gandhy and Khorshed Gandhy. (Photo courtesy Chemould art gallery)

(From left) Shireen Gandhy with parents Kekoo Gandhy and Khorshed Gandhy. (Photo courtesy Chemould art gallery)

What propels both these narratives is the idea of the engaged Citizen from the world of high, West-influenced culture — and which for most of India is as elitist and rarefied as sushi and black truffle — reaching out and trying changes at the level of the ordinary Indian.

As artist Anish Kapoor points out in the film, this idea of the liberal arts catalysing change and which Kekoo Gandhy and his business partner and wife Khorshed Gandhy represented, or at least the attempt to change a larger, non-secular, unjust world, not just by its stories and visuals, but by direct engagement hasn’t unfortunately percolated to the majority of liberals India.

Jerry Pinto’s Citizen Gallery: The Gandhys of Chemould and the Birth of Modern Art in Bombay (2022) is as much about an art gallery and the family behind it as it is about an era when Bombay was a city of artistic and intellectual ferment — and how the city’s creative fire still lingers. Art, perceived as a distant universe understood by intellectuals, ensconced in galleries, can be a myth, Pinto tells us, through the story of the Chemould. He reiterates a truth that still needs reiterating: that Bombay is no less an intellectual city than Delhi or Kolkata.

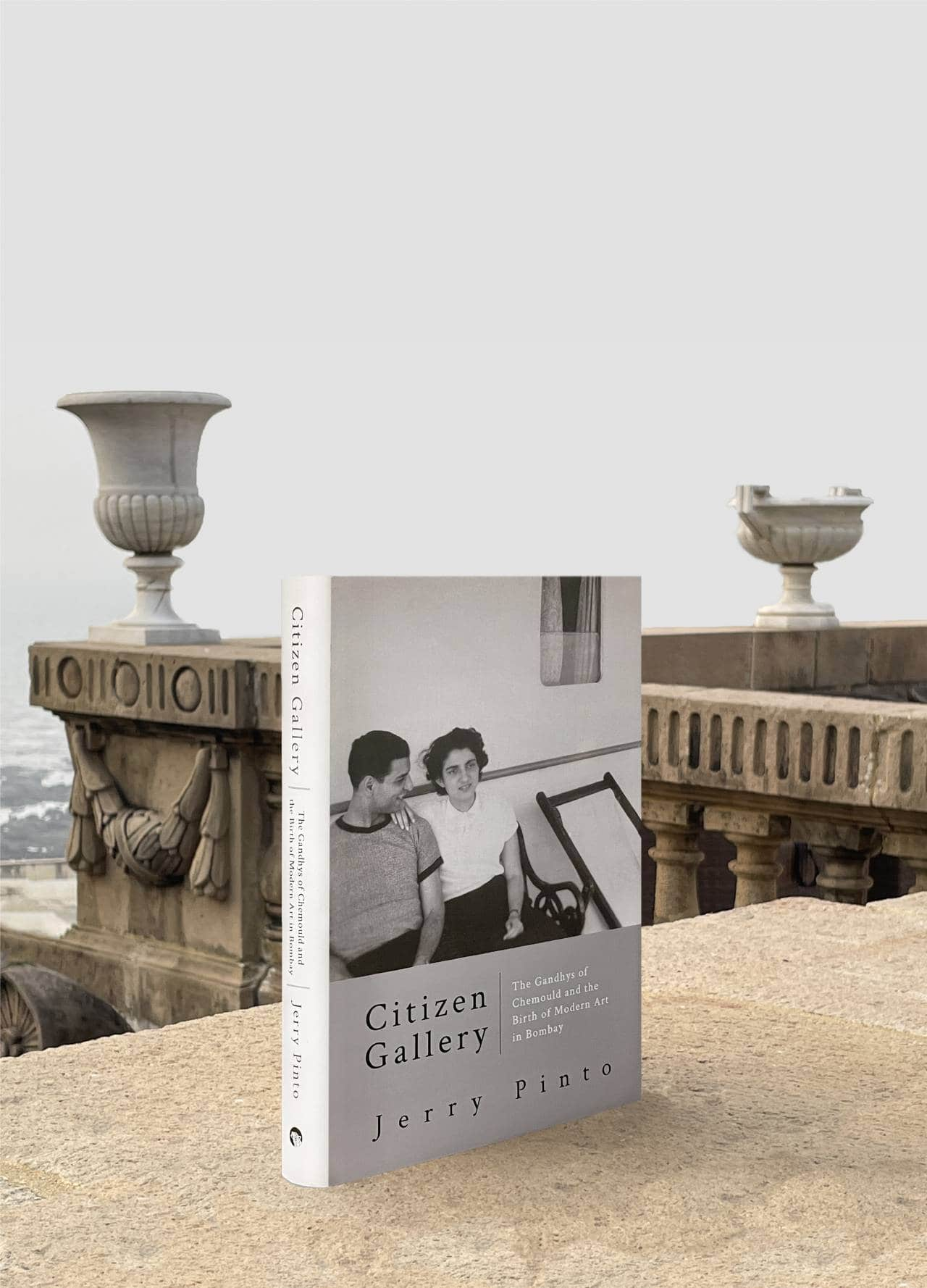

Jerry Pinto's book 'Citizen Gallery: The Gandhys of Chemould and the Birth of Modern Art in Bombay'. (Photo by Aditya Angelo Fernandes)

Jerry Pinto's book 'Citizen Gallery: The Gandhys of Chemould and the Birth of Modern Art in Bombay'. (Photo by Aditya Angelo Fernandes)

Pinto’s rigorous research details how art, and this art family in particular, nurtured and helped evolve art movements that included a discerning, conscientious awareness of the Citizen first, and then artistic snobbery.

He chronicles the Gandhys from the 1950s through to the 1990s, when communal riots ripped the city: “An inclusive India to which we were all heir was non-negotiable to the Gandhys and they fought to restore normalcy to a city that seemed to have run mad at the end of 1992 and the beginning of 1993.”

Pinto, interviewed in the film as Gandhy’s biographer, says, “Kekoo stepped up to the demands of post-Ayodhya Bombay that hasn’t been adequately documented so far. He was unstoppable. He made a nuisance of himself talking to every politician he could put his hands on.”

Once Kekee Manzil was a hideout for Communists, after the Bombay riots of 1992, a milestone that changed the city in irreversible ways, the man on the street that the riots affected, came to Kekee Manzil and its patriarch for help.

In the film, Rushdie, talking to Behroze Gandhy about artist Bhupen Khakhar who again challenged what art could be and whom Chemould introduced to the world with a seminal show in the 1980s, says how his novel The Moor’s Last Sigh (1995) had its fulcrum of the art world following an interaction of a group of artists in the 1970s of which Kekoo and Khorshed Gandhy were a part. In the book, a character of an art dealer is named Kekoo Mody. Rushdie had a long association with Khakhar.

Kekee Manzil in a still from 'Kekee Manzil: House of Art', a personal documentary by Behroze Gandhy.

Kekee Manzil in a still from 'Kekee Manzil: House of Art', a personal documentary by Behroze Gandhy.

The Gandhys weren’t shrewd with their business sense as it appears from the portrait of the couple hat emerges from the book as well as the film. Kekoo was Aman of the moment, a doer, a conversationalist, a medium and facilitatory and Khorshed held fort at home as well as the office, sometimes writing cautionary letters to her husband during hi long travels in Europe that he’d better get back home because she had no money to pay rent. But their associations with artists continued to flourish more and more over the years — it’s a DNA, and it flourishes in the gallery today, at Chemould Prescott Road.

Take the family’s somewhat romantic yet turbulent relationship with India’s most celebrated artist — the artist who is loved and hated by aesthetes and philistines alike. Behroze Gandhy’s film has rare footage of Maqbool Fida painting at Bombay Arts Society, at Kekee Manzil and cycling through Bombay of the 1950s. Once Husain breezed into the family home and demanded to do a family portrait. In 1975, when Husain painted Indira Gandhi extolling her decision to impose Emergency in the country, Khorshed Gandhy wrote a letter to her saying she valued freedom of speech and expression too much to sustain their 30-year-old relationship. They parted ways, only to be reunited in 1992 at the wedding of Shireen and her husband Kurush, when Husain painted a backdrop for the ceremony with Zoroastrian religious figures.

The house interiors as shown in 'Kekee Manzil: House of Art', Behroze Gandhy's documentary.

The house interiors as shown in 'Kekee Manzil: House of Art', Behroze Gandhy's documentary.

Most art books tend to be heavy on the art — its deconstructions and aesthetic catalysts. This is history from the view of the people, and the “first family of modern art in India” — Kekoo, Khorshed and their children, including their daughter Shireen Gandhy who runs the gallery now — that started Chemould, coinciding with the rise of the Progressive Artists. More than a history of art, the book is about a milieu that included artists, authors and critics who lived with purpose in a newly independent, secular India. It is about “impecunious artists” and “great Bombay eccentrics” of the 1950s ad 1960s. Pinto, through interviews and his own experience of living through the Bombay art world’s blossoming, wonderfully distills what he calls “the Chemouldsphere air”.

The film Kekee Manzil tells this same story through a very personal lens. We go into the corners and cul-de-sacs of Kekee Manzil, to the family’s dining table and living room. It’s a heritage home where Shireen Gandhy and her family stay, with many newer additions of contemporary Indian artworks on its walls and Shireen Gandhy’s continued passion to nurture contemporary art. From the small but big-thinking framing shop that Kekoo Gandhy started with on Princes Street to Chemould CoLab started after the pandemic, an extension of the gallery that discovers and supports emerging artists at the start of their careers, Kekee Manzil is a thriving repository of Indian art from the newly cosmopolitan, promise-saturated Bombay of the 1950s’ upto Generation Z’s Mumbai, in which technological, urban and economic swell somehow haphazardly melds into with immigrant and nativist thinking and still manages to ooze a happy melee.

Salman Rushdie and Behroze Gandhy. (Photo: Dev Benegal)

Salman Rushdie and Behroze Gandhy. (Photo: Dev Benegal)

Chemould’s roster of artists include S.H. Raza, Tyeb Mehta, Bhupen Khakhar, Atul Dodiya, Anju Dodiya, L.N. Tallur, Jitish Kallat, N.S. Harsha, Mithu Sen, Pushpamala N, Shilpa Gupta, Nilima Sheikh, Varunika Saraf, Desmond Lazaro, Aditi Singh, Bijoy Jain and Lavanya Mani, and others who represent a range of artistic investigations into India and diverse approaches to material.

The gallery and its legacy are a piece of history entwined with India’s history. Kekee Manzil is a museum of Indian art — and a museum of memories that shaped this family and modern Indian art. It’s even a bit of an anomaly today — and at the same time, a hope — when freedom of speech and expression continue to corrode in insidious ways within a democratic system.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!