Health is the new frontier of luxury. We no longer need wellness gurus to convince us of its currency and futuristic promise. Medicine, health, the body and wellness are on most minds—and timelines—as we slip into the known and “the normal” after the pandemic years. On one level, this fixation is a function of the age, defined by an endless and obsessive search for information. On the other, the marauding virus has reminded us of our mortality and vulnerabilities like never before.

Coinciding with this zeitgeist is the spurt of the medical humanities, a growing metier in the publishing world—so far, it is a narrow but formidably rigorous field with some eye-opening and mind-shattering books. Siddhartha Mukherjee, New York-based oncologist, researcher and author won the Pulitzer for his first book, a majestic biography of cancer titled The Emperor of All Maladies, 12 years ago. He has been at the forefront of this genre ever since, following up with The Gene (2016) and now, The Song of Cell: An Exploration of Medicine and the New Human—473 pages in hardback published by Penguin/Allen Lane. The cell, the tiny building block of all life forms, is his subject. Rigorously researched medical history, memoir and compelling literary non-fiction—The Song of the Cell has the Siddhartha Mukherjee signature.

Coinciding with this zeitgeist is the spurt of the medical humanities, a growing metier in the publishing world—so far, it is a narrow but formidably rigorous field with some eye-opening and mind-shattering books. Siddhartha Mukherjee, New York-based oncologist, researcher and author won the Pulitzer for his first book, a majestic biography of cancer titled The Emperor of All Maladies, 12 years ago. He has been at the forefront of this genre ever since, following up with The Gene (2016) and now, The Song of Cell: An Exploration of Medicine and the New Human—473 pages in hardback published by Penguin/Allen Lane. The cell, the tiny building block of all life forms, is his subject. Rigorously researched medical history, memoir and compelling literary non-fiction—The Song of the Cell has the Siddhartha Mukherjee signature.

The Florida, US-based The Global Wellness Institute (GWI), recognized as a leading source for authoritative wellness industry research estimates that the value of the global wellness economy is around $4.4 trillion (as per research in 2020). It has been a steady growth over a decade—around the same timeline the medical humanities have gained currency in publishing and academia.

In 2014, Rishi K. Goyal, a physician at Columbia University, helped start and became the director of an undergraduate program at Columbia University called ‘Medicine, Literature and Society’, in which he introduces students to the study of health and the body through perspectives, methods and texts derived from the humanities, social sciences and the sciences. He also edits a journal called Synapsis (www.medicalhealthhumanities.com) themed on the intersections of culture, society and health.

When I had met Goyal in 2019 at a British Council Mumbai event, he had told me that the word ‘synapsis’, is what Lewis Carroll, the writer of Alice in Wonderland, also a mathematician, called a portmanteau word—a word within a word. A combination of synapse and synopsis, meant to evoke the complexity of the human brain, the inter-connectivity of ideas, and a broad viewpoint. Medical humanities also fulfil a desire to know ourselves better. It fuses art and science in a pool that has the ability to explain a vast network of interconnected human experiences.

2010 seems to be the year medical non-fiction or the medical humanities was really born. A few months before Mukherjee’s book came out, an American veterinary technician and science writer Rebecca Skloot published The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, a biography of an African-American woman who died in 1951 in a "coloured ward" in Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, US. Her body, tumours from a metastatic cervical cancer blazoning its insides, gave way when Henrietta died at age 31 in intractable pain. She left behind a husband and five children, and also a slice of tissue, a piece excised from the cervical cancer that was her primary tumour. From this sample her cells were cultured. In the years following Henrietta's death, the cell line, known as HeLa in the labs, became an unparalleled research tool. Cells were sent to laboratories throughout the world, bought and sold by research teams. They could be frozen, and their development paused and restarted. Because of them, thousands of experiments on live animals were not needed. Trillions of them are still alive, more than ever grew in Henrietta's living body. They have been employed in research into the polio vaccine, and into the effects of atomic warfare; they were shot into space, used in AIDS research. But the woman who generated them, frequently misnamed, remained largely unknown, and according to Skloot’s book, her family did not benefit at all from the unwitting donation of her money-spinning tissues. In 2017, Oprah Winfrey acted in the film version of the book—available to stream on Disney+Hotstar.

Four years later, the fourth book of Atul Gawande, a surgeon and writer, Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End, came out—a brilliantly moving exploration of illness and death in which he tries to answer philosophical questions such as: Why do we value longevity over what makes life worth living? Do we infantilise the old? Like Mukherjee and Skloot, Gawande’s prose has the clarity and cadence of literary writing.

While these books make the world of medical science and physiology more accessible to the lay reader, take experiences with illnesses, disease and mortality beyond numbers, scans and tests, and enable their authors to cross over to a world previously reserved just for the artistic mind, many authors and novelists have engaged with science for their work. Literary fiction is increasingly setting up shop in the halls of science and the body: Don DeLillo’s work like The Body Artist or the more recent Zero K, which deals with cryopreservation, or Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts, which deals with, among other things, motherhood and gender transitions, or Lucia Berlin’s story collection A Manual for Cleaning Women, which chronicles women who work as cleaning women in hospitals, or Sarah Manguso’s account of a rare neurological condition in Two Kinds of Decay, or Lucy Grealy’s account of the stigmatising effect of multiple surgeries for Ewing’s sarcoma of her jaw in Autobiography of a Face.

Medical humanities graphic novels have enough following to be called a sub-genre: Our Cancer Years by Harvey Pekar, Funny Misshapen Body by Jeffrey Brown, The Infinite Wait by Julia Wertz, Stitches by David Small, Marbles by Ellen Forney—these graphic novels challenge us to see—and not just read—journeys of the body and through it, the mind, illnesses unfolding and how they transform lives in ugly as well as uplifting ways. We see the body in pain and in upheaval; medical paraphernalia like reactions to a CT scan or the minute details of a surgical scar come alive on the panels of these books.

Medical humanities also include a sub-genre of cancer memoirs, which uses light-hearted humour and satire to interpret different kinds of cancer experiences, and it is driven mostly by women who have had breast cancer. The Adventures of Cancer Bitch by S.L. Wisenberg, Cancer Made Me a Shallower Person: A Memoir in Comics by Miriam Engelberg, One-Breasted Woman by Susan Deborah King, My One Night Stand with Cancer: A Memoir by Tania Katan, Cancer Vixen by Marisa Acocella Marchetto.

Machetto, an illustrator who has done a lot of work for The New Yorker, draws what she calls her “fabulista life” among Manhattan’s artsy and high-fashion elite with details in which the comic borders on the absurd. She also shares, in excruciating details, everything about her experience with cancer—all the chemo-induced agony. Cancer victims are clustered up in clouds, and microscopic cancer cells are green rings sticking out tongues and giving you the finger. A review called her book the “inauguration of something marginally novel: Sick-Chick Lit”. My current favourite Indian iteration of this genre is Shormistha Mukherjee’s funny and riveting memoir of her breast cancer journey, Cancer, You Picked the Wrong Girl.

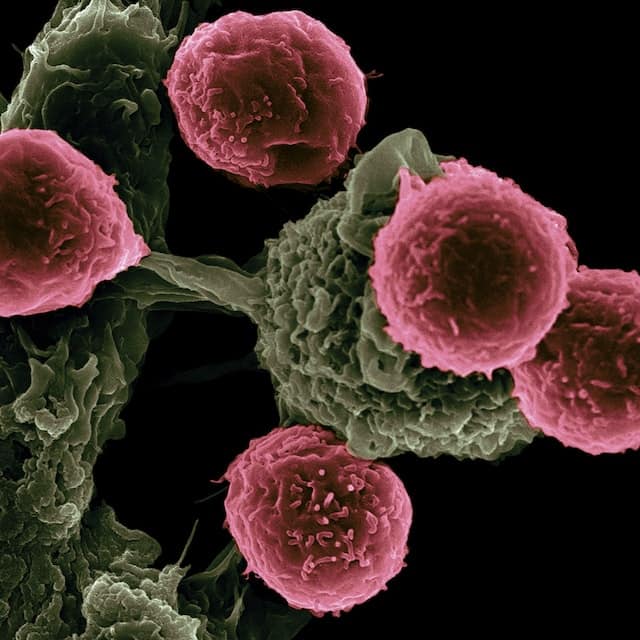

Vaccine immunotherapy. (Image: US National Cancer Institute via Unsplash)

Vaccine immunotherapy. (Image: US National Cancer Institute via Unsplash)With The Song of the Cell, Mukherjee elevates the medical humanities genre to a new height—while celebrating the strides medical science has taken through inventions in cell biology, the tiniest component that drives all life forms and which connects all life forms, his narrative contains the ethical and moral implications of these inventions and the gaps in medical science’s understanding of the interconnectedness of cells.

From the first experiments of cellular organisation and cellular life to momentous events like the first test tube baby, the invention and success of immunotherapy for cancer, depression, up to the novel coronavirus, Mukherjee attributes what he calls the new human—not, as he cautiously points out, AI-augmented, sci-fi versions of the new human, or “Keanu Reeves in a black muumuu” via The Matrix—to advancement in cell biology.

For him, the new human is “rebuilt anew with modified cells who looks and feels like you and me”. He writes, “We’ve altered these humans to alleviate suffering, using a science that had to be handcrafted and carved with unfathomable labour and love, and technologies so ingenuous that they stretch credulity: such as fusing a cancer cell with an immune cell to produce an immortal cell to cure cancer; or extracting a T cell from a young girl’s body, engineering it with a virus to weaponise it against leukaemia, and then transfusing it back to her body.”

What makes it a compelling read is his ability to cross-reference and hyper-reference from the arts and literature to understand human life and cellular life—from the story of Bali and Vamana in Indian epics to the myth of the Hindu goddess Sitala Devi to Charles Dickens, Zadie Smith, Emily Dickinson, Pablo Neruda, Kazuo Ishiguro and Philip Roth.

The triumphalism tempers down with the frustration and failures in medical science, which Mukherjee almost celebrates, revealing that he himself thrives in his endless thirst and pursuit of a cure for cancer. From the book we come know that Mukherjee is experienced not only in cancer research, but also haematology, the foundation of which is cell biology.

“Our vulnerabilities are built out of the vulnerability of cells,” he writes. This thirst defines a scientist’s mind as much as it could define an artistic mind. He makes science human. The coronavirus pandemic underlines his belief in the mysteries and how there’s still so little that medical science knows—“Why does the virus cause more severe disease in men than in women? Again, there are hypothetical answers, but we lack definitive ones. Why do some people generate potent neutralising antibodies after infection, while others don’t? Why do some suffer long-term consequences of the infection, while others don’t? …The monotony of answers is humbling, maddening. We don’t know. We don’t know. We don’t know.”

The book’s epilogue briefly dwells on the moral framework that binds some wild innovations in cellular therapy, like what a Silicon Valley start-up called Ambrosia promises: young blood plasma harvested from youths between 16 and 25 years of age to “supposedly rejuvenate the creaking but wealthy, shrivelling bodies of ageing billionaires”. One litre of “young blood” costs $8,000; two litres is a bargain at $12,000, Mukherjee reports.

I finished reading The Song of the Cell with an exhilarating mix of feelings—alarm, awe and a hopeful uplift. Mukherjee sums up the sublime and dizzying oneness or connectedness of all life forms with piercing clarity, and refulgent prose. It’s a book that will likely be relevant even if and when the “new human” becomes a mundane reality.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.