Rakesh Tiwari, 35, believes that spoken word poetry has broken all barriers. A successful fulltime Hindi spoken word poet who left his BPO job in 2019 without any regrets, Tiwari says the genre allows millennials and the current generation of poets to deal with topics like misogyny, mansplaining, consent, relationships and breakups, “basically expressing all our vulnerabilities and connect with the audience”.

“Spoken word poetry has helped poets get commercially successful,” he says, citing the example of the poetry-based podcast Millennial Kavi (JioSaavn) which has over 90,000 subscribers. “Every time I do an episode on it, I get paid. Today, I have brand collaborations and I write for web series. It is a good feeling.”

Globally, and in India, spoken word has been around in forms like rap, hip-hop, but in its simplest form, it’s poetry that is best recited or performed – unlike traditional or classical poetry. It is a "new form or, in startup lingo, a disruptive way by which youngsters have taken to poetry: as Subodh Shankar, one of the co-founders of the Bangalore Poetry Festival likes to say. “For this edition (on August 27 – 28), we have chosen four spoken word poets from the city to have a session,” he says. “Although personally I don’t consume this form of poetry much, it is amazing to see the energy of the audience during a spoken word session.”

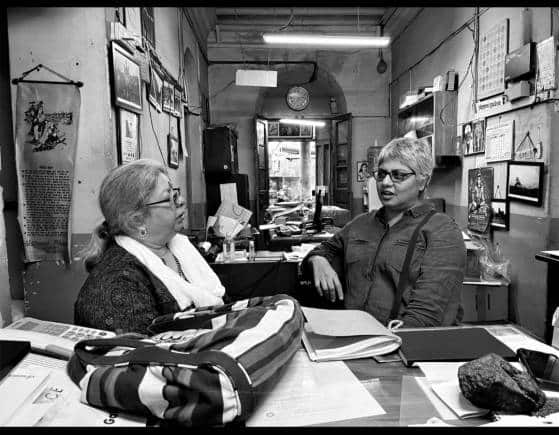

Pratibha Nandakumar and Mani Rao.

Pratibha Nandakumar and Mani Rao.Spoken word is rendered by heart by the poet, not an unfamiliar concept in India traditionally, according to acclaimed Kannada poet Pratibha Nandakumar. “Spoken word is a fancy terminology for a style that has existed in India, be it the long form of poetry in Malayalam rendered in a singsong style or the Urdu poetry rendered in Tarannum chanting style,” she says. “But the younger generation has evolved a new way of rendering which is heavily influenced by hip-hop. Poetry is an art form especially when we talk of rendering. The youngsters own it!”

Many Indian poets, be it Tiwari or the Bangalore-based poet Daniel Sukumar (whose English poems are on topics like mental health and caste inequality), were influenced by a community of poets who were probably performing in their own geographical silos until the Internet and social media allowed access to a worldwide audience. “I would listen to Rudy Francisco and Sarah Kay,” Sukumar says, talking of his influences. “I started doing spoken word after watching poets perform on Button Poetry and Def Poetry Jam.”

Some of the spoken word poets took specifically to social media to reach their audience. Instapoetry became a thing and poets like Rupi Kaur, Lang Leav, Amanda Lovelace made instant connection with young people. A comment left by Brazilian public school teacher Deborah under one of Rupi Kaur’s poems on Instagram said: ‘I used this poem* in my English class and it was amazing!’

Closer home, Tiwari credits The Kommune India and its founders Roshan Abbas and Gaurav Kapur for the video format of storytelling and Simar Singh of UnErase Poetry for promoting this poetry form. When he was performing in 2013 at The Hive in Mumbai, the audience used to be just 8 to 9 people of which “8 would be poets waiting to perform”, he says. But then, things changed. Videos were made and shared on YouTube.

“When videos of spoken word got viral, the form became highly appreciated,” Tiwari says. “People would leave comments saying that they too felt the same (way)... The availability of cheap data made sharing and viewing videos possible, and soon, spoken word reached the youth all over the country.” His 4-minute video of reciting the poem ‘Missing’ – on the various cases of people who go missing every year – has been viewed over 6 lakh times on YouTube.

Explaining the success of spoken word, Sukumar says, “Spoken word has some elements of storytelling and a lot of poetry elements. This poetry is meant for the stage which is why it connects with the people. And it is precisely the reason why spoken word shouldn’t be over 4 minutes long, as people’s attention is short.”

Spoken word, in a way, has bypassed traditional and rigid rules of prosody. “There is an interesting situation here,” Nandakumar says. “More than 100 years ago, there were rigid rules for writing sonnets, etcetera, not only in English but all languages. About 80–100 years back, the shackles were gradually removed and free verse happened. Kannada was one of the earliest languages to embrace free verse or mukta chanda. I remember a Kannada poet performing in Chennai about 40 years back and the audience were surprised to hear free verse and the usage of English words. Soon, other Indian languages embraced free verse which didn’t have any rhyming or meter patterns.” However, the spoken word, according to her, is actually taking rhyming in a different modified form. “It is performance-oriented rhyming and it is very surprising that the current generation has owned it.”

Sukumar uses ‘inner rhyming’ as opposed to ‘end rhymes’ which he feels “make poems so predictable”. The lexicon has changed and Shankar describes it best when he says, “Ultimately, unlike classical poetry, spoken word depends on the poet’s delivery for creating an imagery or impact.”

Subodh Shankar

Subodh Shankar*Stillness - Rupi Kaur

on days you can’t hear yourself

slow down to

let your mind and body

catch up to each other

Tab Likhna – Rakesh TiwariTab likhna jab lage ke

Jo ho raha hai wo sahi nahi

Jab kehni ho koi aisi baat

Jo tumne kisi se kahi nahi

Daniel Sukumar (dedicated ‘To whomsoever is dating or in a relationship with a person with mental illness)…

If it ever comes to a place

where it’s too much for you to take.

Pack your bags, pick up your beds and leave.

But, tell her before you leave.

Tell him, your goodbye.

You see, when a person with mental illness finds love,

he’s always picturing it walking out of the door.

So, this is not the worst that can happen to us,

your absence without a reason is.

But can you stay?

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.