In the early hours of July 31, one got the terrible news of passing away of Subir Gokarn, former deputy governor of RBI (2009-12). He was 60 and ailing for a long time.

My memory of Gokarn goes much before he became RBI deputy governor. He was one of the key advisers to an organisation, in which I worked (Indicus Analytics), though I never met him. Later, I read his Business Standard columns and the reports he wrote as a chief economist for Crisil. Then as he became RBI deputy governor, I, like all other market analysts, followed his speeches and statements to gauge expectations of economy and markets.

Gokarn’s RBI tenure came amidst multiple events in Indian economy and RBI. In September 2008, the world economy was hit by a storm in the name of Lehman crisis. The crisis had left deep wounds in advanced economy and especially in financial markets. The Indian government and RBI had intervened aggressively to stall the effects of the crisis and passed significant stimulus. The Indian economy recovered much faster from the crisis due to both, the structure of Indian economy which relied less on foreign capital compared to other countries and also due to the aggressive stimulus. The United Progressive Alliance government managed to win the elections in May-2009.

Within RBI, the government had appointed Subbarao as RBI governor, just before the Lehman crisis in Sep-2008. As the impact of the crisis waned, Rakesh Mohan resigned as RBI deputy governor in June-2009. Mohan headed the very important functions of monetary policy and economic research, which needed a replacement. After a frenetic search, Gokarn was appointed as the 52nd deputy governor of RBI.

His tenure started on November 24, 2009, more than a year after the Lehman crisis. Even if Indian economy recovered quickly, there was little clarity over the nature of recovery and as a result the stimulus continued. This in the end, paved way for much of chaos in Indian economy. The lingering stimulus led to much higher fiscal deficit and along with really low interest rates fuelled inflation.

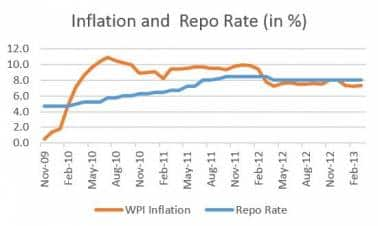

At the time, when Gokarn took office, WPI inflation (the main measure of inflation that time) was just 0.5% and the Repo rate was 4.75%. By March-2010, inflation zoomed to 7% leading to RBI increasing the policy repo rate to 5%. From 2010 onwards till the end of his tenure in December 2012, inflation continued to remain elevated and averaged 9%, almost double the comfortable RBI range of 4-5%. This despite RBI increasing the policy rates to 8.5% in March 2012.

As RBI searched for answers for this elevated inflation, Gokarn came up with the idea of protein inflation. In a controversial speech in October 2010, he said with rising incomes Indians were consuming more proteins in the form of dals, eggs and meat. As supply of these items had not increased with demand, this put upward pressure on their prices and subsequently in inflation. The debate was hardly new as for a long time experts have tried to grapple with the question of whether India’s inflation is due to higher demand, lower supply or central bank activism (as suggested by Milton Friedman).

Gokarn’s speech took the attention back to supply side factors with addition of new source in the form of protein. This was criticised by scholars who pointed to similar rise in incomes and consumption in other countries but not inflation. They stressed that inflation had risen mainly because RBI did not increase its policy rates aggressively enough (termed as baby rate increases). The higher fiscal deficit, also complicated the inflation problem which required even more aggressive rate increases.

These rate increases irked the industry, which complained to the government over higher cost of capital. India was suddenly suffering from its own stagflation where inflation was high and growth rates were low. RBI even cut policy rates to 8% in April 2012, despite elevated inflation. This led to further criticism over RBI’s role as inflation manager. Gokarn’s term was to get over in November 2012, but he was given a month’s extension and resigned from RBI in December 2012. Urjit Patel replaced him as the DG in January 2013.

In 2013, India suffered from multiple problems of low growth, high inflation and high twin deficits (fiscal and current account deficit). When US Fed chief Ben Bernanke announced that Federal Reserve would increase interest rates, the Indian economy went into a tailspin with large capital flight. India was dubbed as one of the fragile five economies, which was impacted severely in the period May-August 2013. In August 2013, RBI published a study which pointed interest rates contributed marginally to the cause of falling investment and growth, trying to absolve its role in the crisis.

That September Raghuram Rajan took over as RBI governor. He along with his deputy Urjit Patel ushered the inflation targeting regime in India in 2015, which has succeeded for the time being in lowering India’s inflation. It is ironical that just before Gokarn passed away, RBI released its Occasional Papers Series, with three of the four papers talking about inflation, the menace which RBI tried fighting under his tenure to no avail.

Subbarao in his memoir Who Moved My Interest Rate?, points that he had requested the government to extend DG Gokarn’s tenure but was rejected. This was perhaps because of RBI’s inability to fight inflation during this time and with fall in growth there was a strong perception of policy paralysis. The government decided to appoint new people to infuse fresh thinking and solutions.

Post-RBI, Gokarn joined Brookings India as director of research. In 2015, he was appointed as executive director on board of the IMF representing India, Bangladesh, Bhutan and Sri Lanka. It is quite amazing that he continued serving the IMF job despite fighting a critical illness. Though, once again his comment on demonetisation, supporting the policy and calling for it to be done frequently to counter counterfeiting and hoarding, raised controversies.

Post-script: In 2011, RBI’s College of Agricultural Banking had organised a two-day workshop on economic policy and developments for bank economists in their campus in Pune. They had invited Gokarn to inaugurate the workshop which was to begin at 8 AM. We were all surprised to see Gokarn reach the venue much before time and eventually waiting for us in the hall! Usually, one expects senior dignitaries to come after the audience but we seldom see the person waiting in the hall. His punctuality and sincerity surprised one and all.

Amol Agrawal teaches at Ahmedabad University. Views are personal.Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.