The Indian Rupee (INR) has shown a fair bit of resilience over the past year, which is all the more remarkable considering that India is one of the largest commodities and energy-importing countries. Broadly, in the past, the USD-INR pair has moved as a result of the US Dollar, the Chinese RMB (CNY), and foreign currency flows, with different intensities at various time periods. Note that foreign currency flows into India do depend on the movements of major currencies, particularly the USD.

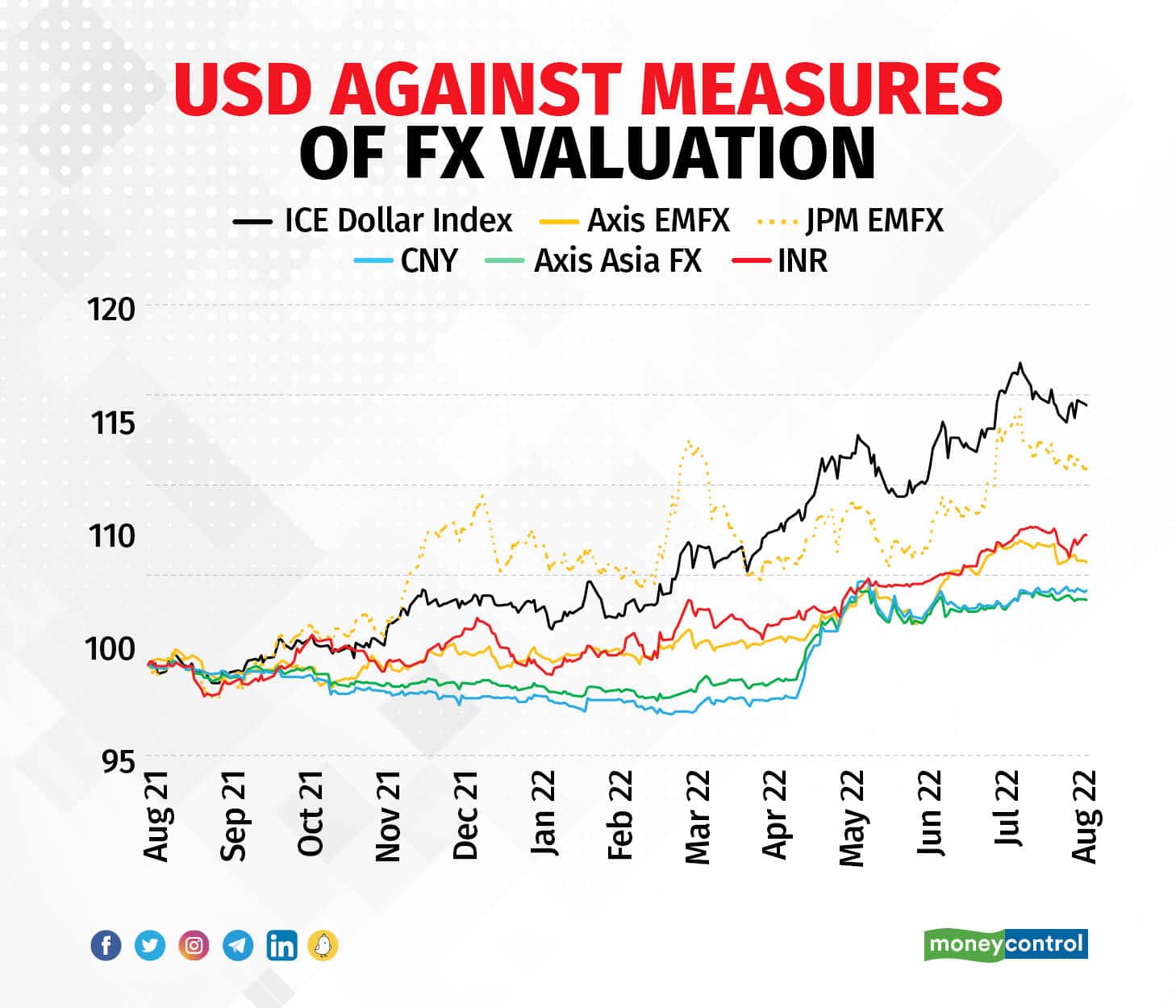

The chart below shows the relative movements of various currency baskets (a move up indicates depreciation).

Since July ’21, the ICE Dollar Index (DXY, the USD against a basket of Developed Markets currencies) appreciated 7.1 percent. The sharpest moves were during November-December ’21, when the US Federal Reserve (Fed) first signalled that inflation might not be ‘transitory’. The second big move was in February-March ’22, with the hostilities in Ukraine, leading to a flow to safe haven currencies. Thereafter started the large strengthening of the USD with the full pivot of the Fed into aggressive tightening of monetary policy, even as the European Central Bank (ECB) was relatively dovish, anticipating an economic slowdown in Europe with the energy and supply chain disruptions. The USD then weakened in May ’22, once the ECB and the Bank of England signalled policy tightening.

From July ’21 to February ’22, the INR had still been relatively stable, despite the start of sustained foreign portfolio outflows since October ’21.

Contrast the moves in the INR to the other emerging market (EM) currencies. The dotted yellow line (in the above chart) is the JP Morgan index of EM currencies (JPM EMFX). This had become significantly more volatile post November ’21 (after the Fed inflation view change). However, this index comprises some of the most volatile EM currencies like the Turkish Lira, Brazilian Real, South African Rand, etc. Stripping out these volatile currencies, an Axis proxy index of more stable EM currencies (Axis EMFX) is the solid yellow line. For the most part, except for short periods in February and May ’22, the USD-INR pair has moved pretty much in line, although realised, volatility of the INR had been a little higher till April ’22.

The final comparison is with our Axis proxy basket of Asian EM currencies (Axis Asia Fx). Till April ’22, this had been more stable than the INR. But notice the co-movement of this basket with the Chinese RMB (CNY). The CNY is largely a controlled currency, but had been allowed to depreciate by 7.1 percent during April ’22, due to various factors like capital outflows, a looming growth slowdown, problems in real estate, etc. April-May ’22 was the period — with a combined depreciation of the DXY and the CNY — that the INR would have faced the most pressure, although the maximum FPI equities outflows were in February and March ’22.

This is where the RBI’s management of the INR shows through, especially the volatility. Although the RBI had started selling USDs in the spot market since October ’21, the months starting March ’22 were the really aggressive sale interventions (other than in December ’21), once the combined impact of the Ukraine crisis hit the INR (as can be seen in the move up from that point in the DXY) and the CNY. The full suite of instruments — spot, forwards (even long maturity) and futures — were deployed, with interventions more focused on spot markets since March ’22. It is evident that despite a large reported $16 bn Balance of Payments (BoP) deficit in Q4 FY22 and an estimated $14 bn or more in Q1 FY23, volatility was more or less close to the stable EMFX basket. Another feature was the guidance of the currency on the lines of this EMFX basket; there’s little point in spending forex reserves fighting against a strong USD.

Going forward, the magnitude of policy tightening that might be required of the US Fed is also likely to have a bearing on the ‘financeability’ of India’s expected BoP deficit, particularly via low portfolio capital inflows. Combined with the likely strength of the USD, this will have an effect on the INR. Hence currency management — in the context of domestic policy operating in an open economy Impossible Trilemma environment — will need to be an active component of the monetary policy toolkit.

Saugata Bhattacharya is Executive Vice President and Chief Economist, Axis Bank. Views are personal, and do not represent the stand of this publication.Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.