India's policymakers may have to wait until 2026 to get an updated retail inflation series that not only accounts for changes in consumer behaviour but also addresses issues plaguing the construction and computation of the index.

The sharp increase in consumer price index (CPI) inflation in January to 6.52 percent — following a tweak in the statistics ministry's usual computation methodology forced by the free provision of foodgrain through the Public Distribution System (PDS) — shed light on one of the many issues that are causing problems with the measurement of inflation in the country.

The cereals issue is the latest in a series of statistical quirks that have affected monetary policy decisions. And these cannot be ironed out quickly.

Housing and HRA hikesBack in 2017, housing inflation as measured by the CPI jumped from 4.7 percent in June to 8.25 percent by December following the implementation of the 7th Pay Commission's recommendation to raise the house rent allowance (HRA) of central government employees by 105.6 percent starting from July 2017.

As house rent accounted for 9.51 percent of the CPI basket, this rapidly pushed up CPI inflation from a record low of 1.46 percent in June 2017 to 5.21 in December 2017. Given that the impact of the HRA hike on inflation was statistical in nature, the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) at the time decided to ignore the jump in inflation.

However, the HRA hike only exposed inherent problems with how the CPI measures housing prices.

As much as 1.3 percent of the CPI basket — more than the combined weight of onion and tomato — is made up of employer-provided dwellings, mostly by the public sector. And rent for government-provided houses depends on who lives in it and their HRA.

"If we measure an increase or decrease in rent when there is a change in tenant of a privately rented house, then such changes reflect actual movements in market rent. However, the movements in rent of government dwelling due to change in resident, has no relation to actual change in rental prices," an RBI staff paper said in November 2018.

The recent cereals episode came to light when economists pointed out that there was a discrepancy in the cereals index of the CPI. If computed by taking the weighted average of its 20 components, the cereals sub-group index was smaller than the one published by the statistics ministry. This difference is due to the manner in which the index was compiled: horizontally by the ministry, and vertically by the economists.

Using the indices for each of the 299 items in the CPI basket, the statistics ministry compiles higher-level indices – sub-group and above – for each state, union territory, and the rural and urban sectors. This is vertical aggregation. To then arrive at the all-India index for these items, each item's index across states, union territories, and the rural and urban sectors is totalled using expenditure weights. This is horizontal aggregation.

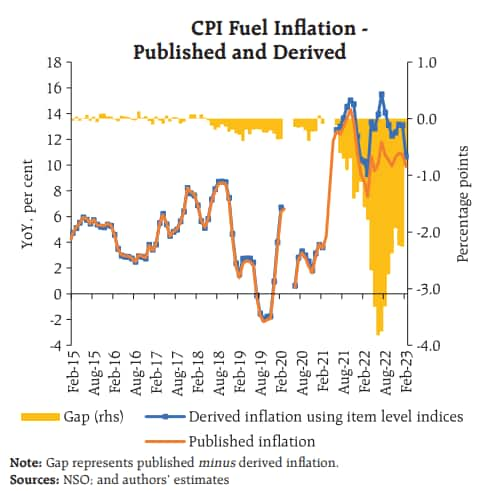

Economists, meanwhile, aggregate vertically from bottom to top – item to sub-group to group to the all-India index – once the CPI data is out. This difference in aggregation led to the discovery of a sizeable discrepancy in the cereals index in January. And before cereals, there was the fuel index causing similar issues as early as mid-2021.

Source: RBI staff paper (Consumer Price Index: TheAggregation Method Matters)

Source: RBI staff paper (Consumer Price Index: TheAggregation Method Matters)The method of aggregation matters because inflation forecasts are made using vertical aggregation.

"…considering the way in which the CPI is constructed, there are bound to be differences between the headline inflation computed and published, even when at an item level indices forecast and published largely tally – the January and February 2023 CPI print was a recent example," RBI staff said in a paper in March.

As monetary policy must be forward-looking, the MPC depends on the RBI's forecasts while making interest rate decisions. And if actual inflation keeps missing forecasts, policymaking becomes more difficult.

Policy changesThe RBI staff paper published in March recommended that the statistics ministry change its aggregation method. However, any change in methodology is usually done when the data series is updated – say, at the time of the base year revision.

Given that foodgrain will be provided for free via PDS for all of 2023, the impact of the internationally-accepted practice adopted by the statistics ministry – when a good or service is provided for free, its weight in the CPI basket gets distributed among other items – will be felt for the whole year, more in some months, less in others.

As of now, there seems to be no inclination to change the methodology, with the 24-member strong Technical Advisory Committee on Statistics of Prices and Cost of Living (TAC-SPCL) – the committee that guides the statistics ministry on inflation measures – having last met in July 2022.

"No, we haven't had any meetings recently… I don't know why it hasn't been held," a member of the TAC-SPCL told Moneycontrol on condition of anonymity.

"Usually, if any major change is carried out in the methodology, then the committee is supposed to meet and endorse it, or the committee will be apprised of the proposed changes… Sometimes, changes are required. The whole purpose is to make the price index realistic… From time to time, it is important to revisit the method and come up with better ways of generating the price index," the member added.

Even if changes were to be made now to the computation methodology, it would "disturb" the entire CPI data series, two people aware of the matter told Moneycontrol.

But then, the only solution is a new and updated CPI series.

New CPI series is far awayA complete overhaul of a CPI series can only be done once the statistics ministry has conducted its Consumer Expenditure Survey (CES). This survey is used not just to revise the base year of the CPI series but also the basket of goods and services – and their weights – for which prices are to be measured.

The current CPI inflation series is based on the 2011-12 (July-June) CES. And the need to update the CPI series has been apparent for some years now.

"The CPI uses consumption weights of 2011-12 that give almost half (the weight) to food. The share of food and cereals is much lower now," Ashima Goyal, one of the three external members of the MPC, told Moneycontrol in February.

"The index needs to be updated as quickly as possible. The MPC has to spend far too much time and effort on prices of various food items that are beyond its influence. I had raised this issue when I joined the MPC but the status quo prevails," Goyal added.

Work is underway to update the series. But its conclusion remains a distance away.

The statistics ministry started work on a new CES in August 2022. While this should end in July 2023, the plan is to conduct back-to-back surveys on account of changes made to the survey's questionnaire, which has been split into three to make it less bulky and time-consuming for respondents to answer in one sitting.

As such, the second of these back-to-back Consumer Expenditure Surveys will only be completed in July 2024. Once the fieldwork is done, a minimum of six months may be needed to get the surveys' results. And only then will work on updating the CPI series begin.

"So the best case scenario is August-September 2025. The series should ideally be launched starting in January. So January 2026," a person aware of the process told Moneycontrol.

The current CPI inflation series was released in February 2015, more than two-and-a-half years after data collection for the 2011-12 CES was completed. Now, however, the use of tablets in data collection could speed up the process slightly. But not fast enough for the current MPC, whose external members' tenures will end in late 2024.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.