Women’s lives, especially in South Asia, have been, for aeons, shaped by one phrase: What will people say? In Rafina Khatun’s documentary film Log Kya Kahenge (What will People Say), 24-year-old RJ Gulnaz uses community radio to become a voice for the voiceless in Ahmedabad. Her show Sharenama exposes injustices, fosters unity, and challenges prejudice. Amid activism, she fights for her own freedom. The film was made possible with the Uncode fellowship given by the nascent Delhi-based Rough Edges, which has started its travelling events Imprints, the first of which was on Sunday, March 9, at Gurugram’s Museo Camera, where they brought RJ Gulnaz in a tête-à-tête with RJ Sayema and feminist historian and filmmaker Uma Chakravarti. A day prior to that, on International Women’s Day, Khatun’s film, along with a package of Rough Edges films, screened at the Asian Women’s Film Festival, which was in its 20th year this year, organised by IAWRT (International Association of Women in Radio and Television) Chapter India at Delhi’s India International Centre (IIC).

Belda/Kolkata-based Khatun, a final-year editing student at Kolkata’s Satyajit Ray Film and Television Institute (SRFTI), was working with Drishti, an NGO in Ahmedabad, when she received the Uncode fellowship grant, aimed at exploring and visibilising diverse and complex experiences of gender. “When I first met Gulnaz in Ahmedabad, I was deeply impressed by her resilience, the place she comes from, the battles she fights every day against patriarchy. Her story felt so similar to mine. When I heard about the grant, I knew I had to bring this story out, not just for her but for countless girls like her. While filming, my female crew and I faced restrictions and even threats. Gulnaz herself was pressured by a powerful goon, making some realities too dangerous to capture. That’s why such films are crucial, they amplify the courage of women who drive change,” says Khatun, 29, adding, “both Ridhima (Mehra) and Tulika (Srivastava), at Rough Edges, remained patient, supportive, and optimistic. More than professional, we built a personal bond that made the entire process more meaningful,” she says.

Four-time National Award-winning independent filmmaker Lipika Singh Darai adds, “Rough Edges is a bold step taken by Riddhima and Tulika, who bring a wealth of experience from their previous association with PSBT (Public Service Broadcasting Trust). It fills a crucial gap in documentary production in India. I’m not sure if I would have ever willingly chosen to seek support for such personal essays from any other organisation. I doubt anyone else could have backed this tender, intimate work of mine from India with such effortless understanding and profound care.”

Darai’s International Film Festival of Rotterdam (IFFR)-premiered epistolary essay film B and S, which tells the story of friends B (Biraja) and S (Saisha) negotiating the meaning of transness, love, loss, friendship, building a home together as friends, and violence, was made with the Rough Edges’ fellowship.

“They gave a small fellowship but it came at the perfect time when it was the time for me to shoot,” says Bhubaneswar-based Darai, 40, whose reluctance to approach producers previously stemmed from her hesitation about creative interference. “I have a unique way of editing these essay films that resemble letter writing — editing in one continuous flow for a few days, with minimal changes or manipulation to the original cut. This method might not be easy for producers to accept, but they (Rough Edges) showed a great deal of confidence in me and my process. From the very beginning, with a clear pre-production plan, we were on the same page, right through to the end. At certain points, I had some very nuanced and complex doubts about a few depictions in the film, but we were able to resolve them together,” says Darai, a 2010 Audiography graduate from Film and Television Institute of India (FTII), Pune, who’s briefly worked with Mani Kaul.

Of course, Darai knew Mehra and Srivastava from before — as the force behind PSBT which produced her long documentary Some Stories about Witches (2016). “The film was aired on TV without any censor edits, which was a significant achievement for us. I believe it required a lot of behind-the-scenes work, which was expertly handled by them,” says Darai, who traces her roots to the indigenous Ho community.

The story of the recent-born Rough Edges Arts and Media goes back in time. The Delhi-based feminist documentary-support initiative came into being in 2022 — thanks to the COVID-triggered lockdown — under the stewardship of Tulika Srivastava and Ridhima Mehra. But the seeds were germinated in the 2000s, when the two were programming and producing documentaries at Rajiv Mehrotra’s not-for-profit PSBT, run in partnership with Prasar Bharati, India’s public broadcaster.

The duo played a key role in making the PSBT story happen. Srivastava joined PSBT in 2000 after a stint with Pritish Nandy and Mehra brought in her gender activism and learnings from an informal queer group of students, activists and feminists using films and other media to stir up conversations around gender and sexuality. Mehra harboured a dream to create a space like a Zubaan (feminist publishing house in Delhi) for documentary films in India. To look at feminist filmmaking and feminist processes in the creation of art and how that art speaks in a deeply unequal and inegalitarian world. “We were very clear that we were going to work with women, queer and non-binary artists. That is the kind of stories and voices we wanted to highlight and foreground. We wanted to make a dent in the understanding of what is art, what is worthy of becoming art and who should have access to art,” she says. The two women brought 20 years of their experience at PSBT to Rough Edges.

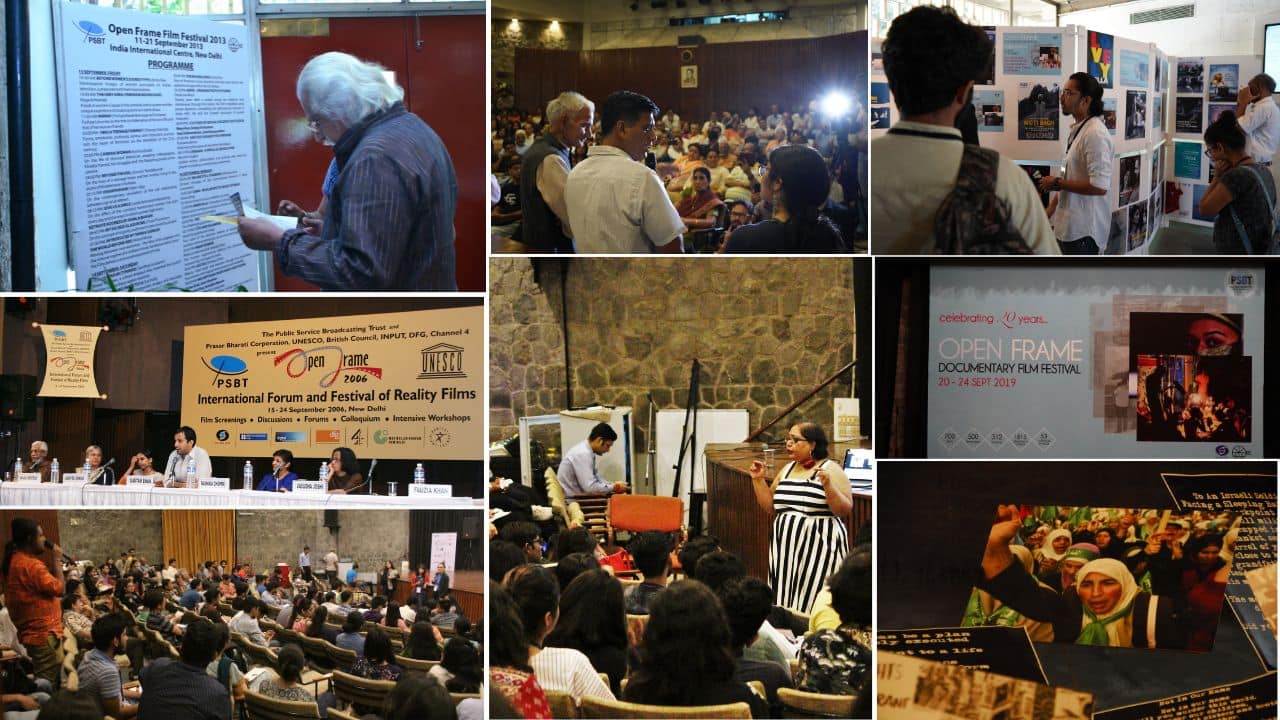

At PSBT, gender-focussed programming increased after “Ridhima joined, and PSBT was probably one of the first organisations (in the country) to have had an International Gender and Sexuality Festival in 2007,” says Srivastava, “From there, it became even clearer that it was not just about the kind of filmmakers we were working with but also the themes and the subjects we wanted to really amplify. There was a shift in the kind of films we started doing after 2008, we tried exploring different grants, and [programming] for Doordarshan. It did push the boundaries and paved the way for us to then go on till 2019 with different films on different subjects.” Through regular commissions, screenings, and the Open Frame Film Festival, PSBT mobilised voices, from the earnest to the marginalised, to use films beyond a creative output, to stoke dialogues on the need for social change.

Stills from PSBT's Open Frame Film Festivals over the years. (Courtesy Rough Edges)

Stills from PSBT's Open Frame Film Festivals over the years. (Courtesy Rough Edges)

At PSBT, “we were funded by Prasar Bharati which is a non-governmental body. We were able to work rather independently of any interference and filmmakers were able to make what they wanted. I’m not even aware of many bodies doing this kind of work,” says Srivastava. PSBT’s launching grant came from three sources: its own corpus, Ford Foundation in the beginning and Prasar Bharati as primary funding partner. “Then we had other partnerships, with UNFPA, UNDP, MacArthur Foundation, the Ministry of Environment, Public Diplomacy Division, and the Films Division, which was under the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting. In 2012, we (PSBT) started working with (the erstwhile) Films Division (FD). A big chunk of, around 98, films got made in 2011-12,” Mehra adds.

In 2022, four government film bodies, including Films Division, faced closure and merger with National Film Development Corporation (NFDC). Rafina’s elder sister and editor-director Farha Khatun who has been an employee of the now-defunct Films Division since 2016, where FD has produced four of her short films, is still awaiting redeployment, since the FD closure/merger, and is unsure if there will be any department in the future that will support the kind of films she has been making.

The lockdown was also the time when PSBT was seriously considering what it would do in the future and how, because their grants had ended, and grant talks with Prasar Bharati were rudimentary, says Mehra, “PSBT needed to have more broadbased conversations in terms of other kinds of financial support and creating an infrastructure.” It was end of the road for Mehra and Srivastava, who couldn’t see a foreseeable future at PSBT, one they could work hard towards building. The impulse, desire and need to set up Rough Edges meanwhile was only becoming stronger. Ties, both professional and emotional, were severed, as they embraced a life of freedom and anxiety.

Malayalam filmmaker Adoor Gopalakrishnan and actress Sharmila Tagore attending the Open Frame Film Festival in Delhi. (Photo courtesy Rough Edges)

Malayalam filmmaker Adoor Gopalakrishnan and actress Sharmila Tagore attending the Open Frame Film Festival in Delhi. (Photo courtesy Rough Edges)

Mehra notes that PSBT, the organisation, didn’t change per se but the environment that one was working with and in changed completely. “People were worried about the kind of things we were saying or the films would potentially say. There was an atmosphere of self-censorship that we thought was beginning to take shape. We started hearing things about doing a certain kind of film, which would be non-controversial and apolitical,” she says, adding, “there is no such thing as apolitical”. As an organisation, Srivastava, Mehra and Mehrotra were on the same page. “It was the external environment in which there was always an atmosphere of anxiety. This is what the system has done to you, that even when you are in the right, you are still full of anxiety,” Mehra adds.

“Filmmakers who were critical of PSBT,” says Srivastava, “are now struggling to find spaces where they could go out and make the film they wish to.” That criticism was also valid, Mehra concurs, because the filmmakers couldn’t see what was happening at the other end. “Having said that,” she adds, “what PSBT did was wonderful. Now this country has no other body which actually can or is able to do what PSBT did. For us, I think PSBT was a very good learning experience to further improve on creating that sort of a space for filmmakers. The histories we have had and our lessons there, we don’t want to erase that responsibility. Even the negative experiences have actually taught us how we wanted to do things differently. We operated within compulsions and institutional structures but were still able to push some things. You can’t jump and smash it all out. You have to start making smaller dents where you can and then enlarge those,” says Mehra.

But why call their initiative “rough edges”? I ask. Srivastava laughs and says, “We are very rough-y and edgy.” An apt name since the ride for edgy documentary films in India has never been smooth. In a way, “embodying roughness, or the state of the universe, and the edgy critical subversions to uphold the hope of the world,” adds Mehra.

They want to solely work with non-fiction films. “Look around us, where is the money for documentaries? There’s very little State support for documentary films. Then there is censorship,” says Srivastava, as Mehra adds, “But in terms of how people respond to documentary, the love for the documentary has actually not been shaken. There has been an enlarging of not just the makers of documentaries, but the seekers of it as well. We owe a lot to the early documentary movement in India and the underground networks of documentary screenings that allowed that to flourish.” “OTT platforms are a no-go area completely because they wouldn’t even look at films which have been made at paltry budgets such as under Rs 2 lakh. If you don’t have funds, you cannot put the films out,” says Mehra, “So, there is an ecosystem that PSBT helps support. There is already an ecosystem of distribution, which “may not be a formal channel but documentaries continue to be seen in many different sizes of groups and audiences.” Earlier, in 2000s, the spaces one could go to watch documentaries at, in Delhi, were the IIC (India International Centre) and Habitat (India Habitat Centre).

The real crux of the massive problem, however, remains funding. It’s sadly inversely related that “as the love for the documentary grows, real and visible support and funding for it is declining. It’s really a strange story,” says Mehra. If PSBT gave Rs 3-4 lakh for a half an hour film and Rs 6-7 lakh for a 58-60 minutes film, Rough Edges have been able to give Rs 2 lakh per commission under Uncode fellowship at the moment.

Two rounds of their Uncode fellowships, for women, trans and queer-identifying filmmakers, are complete. And 10 films have been produced. In their first call itself, they got senior filmmakers submitting proposals. “It goes to show that there is such scarcity of funding,” Srivastava says. At the moment, Rough Edges is struggling for funds and is open for collaborations, even corporate ones if their values and vision align. “We are looking for partnerships with those who believe in the kind of work that we are doing and understand being a feminist space. We are open to funding as long as it does not come with strings attached in terms of any diktats on our creative control: what the films are going to be, who is going to make the films, what is the subject going to be. It’s very difficult to find money like that,” says Mehra. “We look at all money as public money, but when is it spent on films as a legitimate form of public policy or intervention?” The two women have been working without a salary for more than a year now.

With PSBT commissions, however, “even if filmmakers primarily got funding from outside, the copyright (and telecast rights) used to always be with the donor, which is Doordarshan/Prasar Bharati. A lot of the funders probably didn’t want to come on board because they would not get the kind of rights they would actually want in return of funding a film. This was something PSBT was not able to negotiate on,” Srivastava says, “But people now say, there is no body to which they can turn to with a proposal, for funding.”

Mehra adds, “At Rough Edges, the copyright vests with the filmmaker. For the first year, those rights are given to us by the filmmaker as per our contracts and after one year of the submission of the films, the copyright is theirs and they remain the original copyright holder through the life of the film. That was a radical departure from a lot of other creative work that we see happening around us and certainly at PSBT.”

What also sets Rough Edges apart is that they “don’t ask for censor certificates. It’s up to the filmmakers. If they want to enter in the National Awards, they will have to get a censor certificate,” says Srivastava. Mehra adds, “Smallest of festivals asks for it (censor certificate or an exemption) for screening your film. Even in colleges. So, how far do you escape this?” At the Open Frame festival, they used to get a list of all the films exempted or not.

The idea at Rough Edges is “to, first, create a substantive and critical body of work around experiences of gender, whether in climate change, architecture, people’s movements, histories of feminism in India, labour and livelihood, seen from a feminist and queer perspective, respecting the multiplicities of filmmakers’ politics and locations. And, then, to use them for conversations around film and everyday gendered lives in groups of small and big audiences across India. We are not obsessed only with film festivals but are also looking at smaller spaces of college tutorials, community groups, workshop spaces or trainings,” says Mehra.

The scale now is drastically smaller than PSBT, where Mehra and Srivastava were commissioning/producing 100 films at a time in certain years. The engagement level was formal and deadline-oriented: a questionnaire form, email interactions, follow-ups on scripts, weekly telecasts. Now, the interactions are far more engaging and enriching. “We want to invest a lot of time and attention to the process,” says Mehra as Srivastava adds, “We have met all the filmmakers, through different stages of film development. It’s been a collective and emotional process. We are not mere commissioners or producers.”

Loosely put, it is mentoring. But a prolonged one, depending on case by case basis. “The more intimate the process of creating art, the more affirmative it is and the more powerful it is politically and creatively,” Mehra quips. The likes of such veterans as Priya Sen (Pari) and Ruchika Negi (Humare Beech Mein, along with co-director Rajkumari Prajapati) might just need a sounding board while those making their first or second films might need greater hand-holding. Formal film training of filmmakers, however, isn’t required but they must have something to say “with experiential authenticity and passion, about their own lives, their larger communities and cultural-political locations.” Riding on their goodwill, they also, sometimes, on behalf of the filmmakers “write to festivals requesting waivers (submission fees at some of the A-grade festivals can vary from $20 to $100) and suggesting films which might be potential fits on these festivals.”

A majority of the films produced thus far by them train the lens inwards, into the personal: spaces and relationships, “we see a turn towards the inward instead of looking at the larger public, civil, or political outside. The cameras are trained into filmmakers’ homes, to the micro of their lives. While the personal as political is hugely interesting it is also a commentary on why people are not looking outside and calling things black and white,” Mehra says.

If Humare Beech Mein, shot on mobile phone cameras in western Uttar Pradesh, seeks to explore the positions of Prajapati, a social activist from Lalitpur UP, and Negi, a documentary filmmaker and educator from New Delhi, within the stratified structure of caste, Prachee Bajania’s Gujarati film Umbro/The Threshold beautifully clubs together stories of women in their everyday and how they find little moments of courage, resilience and strength. It has won the Best Documentary Award at the Beijing International Film Festival, as part of their Reel Stories category, and won at the International Documentary and Short Film Festival of Kerala (IDSFFK) last year.

Documentary filmmakers who received UNCODE fellowship (clockwise from right) Prachee Bajania's (centre) 'Umbro' won at IDSFFK 2024; Rafina Khatun; Priya Sen; Rajkumari Prajapati; Ruchika Negi; Nikita Parikh; Lipika Singh Darai.

Documentary filmmakers who received UNCODE fellowship (clockwise from right) Prachee Bajania's (centre) 'Umbro' won at IDSFFK 2024; Rafina Khatun; Priya Sen; Rajkumari Prajapati; Ruchika Negi; Nikita Parikh; Lipika Singh Darai.

In Nikita Parikh’s Making Space, in the small, chaotic neighbourhood in Ahmedabad, 16-year-old Alsana carves her own little space, within her own home, speaking of her dreams, and her reality as a young Muslim woman, and as a child being forced to live in a neighbourhood not of her choosing, near a garbage dump, where her family had to relocate. She puts out some of the most potent debates on everyday secularism. Warm Shadows/Nighiyaan Chhavan by Aakash Chhabra (Mintgumri) is a deeply personal hybrid film, co-produced by Sanjay Gulati (Girls Will Be Girls, Laila Aur Satt Geet; Mehsampur) and Neeraj Pandey, where Sheeba Chaddha plays the filmmaker’s mother.

“We want to do something in Delhi, ideally go the whole hog, call every filmmaker and all. But if that isn’t possible then we’ll probably just do single screenings. It’s not that we’re going to wait for that ideal moment,” Srivastava says. The moment arrived this weekend with their first screenings and conversations at Imprints, which aims to combine “the transformative imprints of films on our memories, lives and cultures with interrogations on gender and its inescapable imprints on our histories, beings and bodies,” adds Mehra. Next stop for Imprints is MAP (Museum of Art and Photography) Bengaluru on March 15. In their second innings, the two women are going back to the basics, to make small dents and then enlarge them.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!