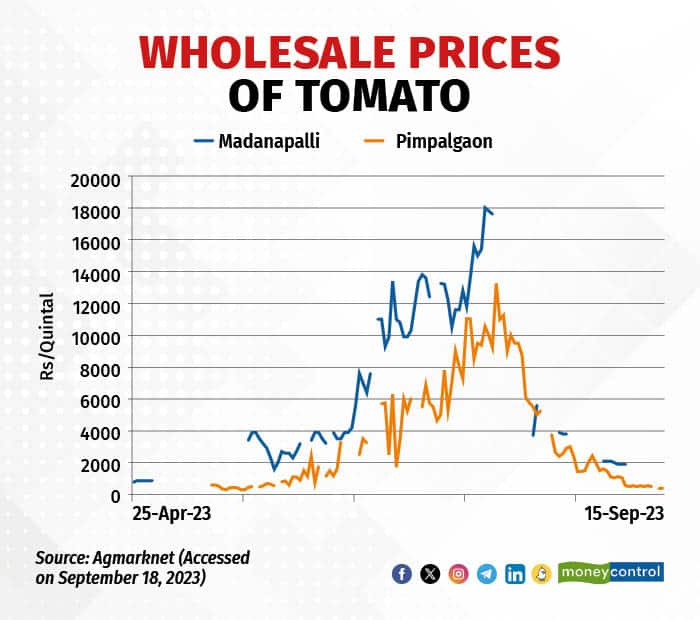

One of the unresolved subjects in the agriculture and horticulture economy is how to shield farmers from low prices. In August, wholesale tomato prices in Pimplegaon (Maharashtra) and Madanapalli (Andhra Pradesh) soared to touch Rs 2,175 and Rs 3,173 per quintal, respectively. Electronic media reported it extensively and the government acted swiftly to cool the prices. In September, wholesale prices crashed to Rs 537 per quintal at Pimplegaon and Rs 1,321 per quintal in Madanpalli. Consequently, retail prices also crashed to about Rs 27 per kg (Delhi).

In the case of onion, the all India wholesale prices crashed from Rs 2,710.62 per quintal in December 2022 to Rs 1,393.96 per quintal in March 2023. Likewise, potato prices at the all-India level crashed from Rs 2,759.65 per quintal in January 2023 to Rs 1,726.33 in March 2023.

Curiously, the media coverage of price crash is generally not as intense as that of the price rise. For a variety of reasons, the government action when prices crash is also not as strong when prices rise. In this article, we explore the reasons for this dichotomy.

Freezing For Future

Most horticultural produce is highly perishable and only a few commodities such as potatoes and apples can be stored for any significant duration. The most successful primary processing of vegetables has been of green peas through individual quick freezing (IQF) procedure. This allows peas to be stored for a long time, making IQF peas available round the year. In fact, peas have been successfully processed for two decades. Until processing became popular, peas were consumed only in fresh form.

Food processing units purchase peas from farmers during the peak arrival season to process and store in cold chains and then sell throughout the year. In recent years, the IQF procedure has been used for sweet corn and cauliflower. On a much smaller scale, broccoli, onions and carrots are also frozen for consumption at a later date.

It is possible to similarly treat some other vegetables through IQF but Indian consumers have not accepted them so far. The National Egg Coordination Committee (NECC) created the market for poultry products and Amul expanded the market for milk. However, the government and big corporates have done very little to develop the market for frozen or minimally processed vegetables. Therefore, prices crash at the time of peak arrival of fresh vegetables in the market, and quite frequently, farmers do not realize a remunerative price.

Tomato is a good example of this trend (see graph). Tomato wholesale rate fell to only Rs 537 and Rs 1,321 per quintal in Pimpalgaon and Madanpalli, respectively, in September. The farmers may not even realize the cost of cultivation of tomatoes, which was 9.42 per kg in 2020-21. It may have risen higher over the last two years. In such a situation, there is no government support to tomato growers.

Gaps in Data

Agmarknet is the major source of data on wholesale prices, but there are gaps in the data published – which makes the price graph look incomplete. The missing entries could be due to the absence of trading on those days or the failure of APMC employees to enter the data on the portal.

It must also be pointed out that the major source for data on retail prices of tomatoes is the portal maintained by the Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution. We accessed the portal several times on September 22 and 23 September, but we were not able to generate variation reports for daily prices, average prices for the month and month-end prices. We were also not able to obtain the variation report of retail prices of tomatoes for the selected time span (April 1 to September 20, 2023). However, on September 4, we generated the monthly retail price reports for gram and onion from the same portal.

Market Intervention

In the case of potato, governments exercise control as it is stored in cold storages and they are controlled through state legislation. For example, UP has enacted The Uttar Pradesh Regulation of Cold Storages Act, 1976. West Bengal regulates cold storages through The West Bengal Cold Storage (Licensing and Regulation) Act, 1966. When there has been high inflation in potato prices, state governments have imposed restrictions on their movement. Such actions are not possible in the case of highly perishable produce like tomatoes as they are not kept in cold storages.

In the case of onions when prices dropped, the government used Nafed to purchase the same from the open market by using the Price Stabilization Fund (PSF). If there were any losses in this operation, PSF would take care of that. When onion prices soared, the Union government used Mother Dairy booths and Kendriya Bhandars to sell kitchen staple below market prices. But, a similar infrastructure is not available in most other cities. And it is just not feasible to distribute highly perishable vegetables like tomatoes at lower prices in rural areas.

Not having much choice, the government resorts to the Essential Commodities Act to impose stock limits. Going forward, the presence of farmer producer organisations and cooperatives can help by setting up small cooling chambers in the producing areas. Linking them to urban markets can boost farmers’ price realization to some extent. But in the long run, a solution will come through improved and cost-effective IQF and cold chain technology which will prolong the shelf life and make it possible to store such perishable vegetables for a much longer period.

Siraj Hussain is a former Union Food Processing and Agriculture Secretary. Kriti Khurana is a PhD scholar of economics at BITS Pilani, Hyderabad. Views are personal, and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!