The Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana (PMGKAY), which was started as a means to distribute free foodgrains as part of the COVID-19 relief package, was discontinued in December 2022. The government announced the distribution of free grains through other means, but this does not make up for the large demand for the erstwhile scheme or the decrease in funding for foodgrains to the poor.

PMGKAY was discontinued after being implemented for 28 months. Instead, it was announced that the subsidised foodgrains which were provided under the National Food Security Act (NFSA) 2013, would be free-of-cost from January to December 2023. This new scheme has coincidentally also been named PMGKAY.

Since 2013, NFSA guarantees a right to nutritional security, by providing adequate quantities of quality food at affordable prices, and covers almost two-thirds of Indian citizens. There are two categories under NFSA: a) Antyodaya Anna Yojana (AAY), which constitutes the poorest of the poor, and b) Priority HouseHolds (PHHs).

It is also important to understand the change in entitlement to get a full picture. Pre-pandemic, every month, an AAY household could receive 35 kgs and PHHs could get 5 kgs of foodgrains per person, at subsidised rates via NFSA. After the introduction of the original PMGKAY, in addition to the regular quota of NFSA, all households could avail of 5 kgs of rice/wheat and 1 kg of preferred pulses free-of-cost. But starting from January 2023, only regular NFSA entitlements are free, without any extra allocations.

Consider a family of four: during COVID-19, an AAY household received 55 kgs (35+20) and PHH received 40 kgs (20+20) monthly. But now, under the new PMGKAY, the AAY family will get 35 kg and a PHH, only 20 kg per month, albeit for free. In short, the amount of foodgrains available for PHHs would be halved and any extra grain they purchase will be at market price, which is significantly higher than NFSA prices.

The average retail price of rice was Rs 38.81 per kg on February 17, 2023, (according to Ministry of Consumer Affairs data) while under NFSA it had to be purchased at Rs 3 per kg.

Since AAY constitutes only 11 percent of the 80 crore persons covered under NFSA, approximately 71 crore of the beneficiaries will see a large reduction in their yearly foodgrain allocation.

Data from the Department of Food and Public Distribution reveals that although the allocation of foodgrains reached a record high of 1,002 lakh tonnes in Financial Year (FY) 2021-22, this was mainly due to additional allocations under PMGKAY. In fact, normal allocations under NFSA for the same year were slightly lower than in FY 2017-18 and FY 2018-19.

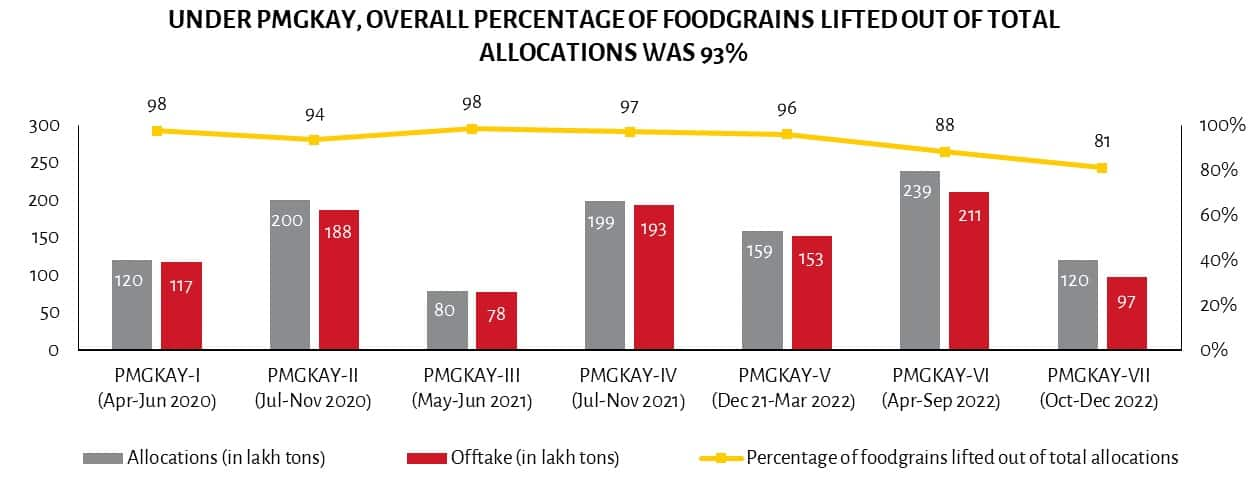

According to a working paper by the International Monetary Fund, PMGKAY allocations played a key role in limiting extreme poverty in India in FY 2020-21. This is also seen in the high percentage of both foodgrains lifted and distributed under the scheme. Offtake or percentage of foodgrains lifted out of allocations, which is done by state governments, stood at 93 percent for the totality of PMGKAY. Similarly, foodgrains distributed to households after offtake was 96 percent for all phases of PMGKAY (till November 2022).

Sources: PMGKAY - I to V, PMGKAY - VI, PMGKAY - VII

Additionally, the stock of available grains was almost double the required norm in 2022, which has consistently been the case for the past few years. For instance, the buffer norm as on April 1 should be 210 lakh tonnes, but in reality, it was 513 lakh tonnes in 2022, 144 percent more than the norm. Even if there is a fall in agricultural yields in FY 2023-24, the high buffer stocks should allow for the continuation of the old PMGKAY for another year.

Now, the question arises: Does the government have enough resources to continue the old PMGKAY? In terms of monetary funding, the total outlay cost for PMGKAY from FY 2020-21 to FY 2022-23 was Rs 3.91 lakh crore for 1,118 lakh tonnes of foodgrains, or Rs 350 crore per lakh tonne. Using the allocation figure from FY 2021-22 of 549 lakh tonnes of foodgrain, the calculated cost of providing free foodgrains for a year was an estimated Rs 1.92 lakh crore.

But FY 2021-22 Revised Estimates (REs) for the Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution (MoCAF&PD) stood at Rs 2,86,219 crore. Thus, the removal of pandemic-related allocations is estimated to save the government Rs 94,332 crore. This can be seen in the budget allocations for FY 2023-24, which are 31 percent lower than both FY 2022-23 and FY 2021-22 REs.

The government’s reason for discontinuing PMGKAY has been an improvement in economic conditions but it is unclear whether this is the situation though. The unemployment rate in December 2022 was 8.3 percent, the highest in the last 12 months since February 2022. Moreover, in this upcoming year, the Russian-Ukraine war will continue pushing inflation and massively increase food prices.

Economic factors can severely hamper one’s ability to purchase food and are mentioned by the World Bank as dimensions that impact food security status. Without the surety of extra foodgrains in 2023, the discontinuation of the old PMGKAY is likely to lead to worsening food security in India.

Jenny Susan John is a Research Associate with the Accountability Initiative team at the Centre for Policy Research. Views are personal and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.