Ashish Anand, the reclusive CEO and managing director of DAG offers a simple reason behind the gallery’s ongoing show, A Place in the Sun: Women Artists from 20th Century India: “I have noticed that viewers and critics always make it a point to ask about the representation of women artists in our exhibitions. I am, therefore, delighted to share a complete exhibition on women artists with them. Their contribution to Indian modern art has been seminal and their recognition needs to be acknowledged. …Each of these women artists have come up the difficult way to find a well-deserved place in the sun.”

Artist Anupam Sud at work.

Artist Anupam Sud at work.

The show includes works by 10 artists — Devyani Krishna, Zarina Hashmi, Madhvi Parekh, Shobha Broota, Anupam Sud, Gogi Saroj Pal, Latika Katt, Mrinalini Mukherjee, Navjot and Rekha Rodwittiya — all of who came into their own as artists in the 1960s and 1970s. It was a time of great creative ferment all over the world, and the two leading art institutions of the country, the JJ School of Art and the Baroda School of Art, were like cradles of a new generation of artists and critics who not only broke away from sentimental, mostly ornamental art of landscapes and still life that best suited a drawing room wall, but also began charging their art with their own relationships and opinions of the world around them. The 1960s were really the decade when paintings and sculptures became expressions of an individual as well as the social realities that shaped her or him.

Much of art discourse until the 1990s excluded a majority of Indian artists. Women artists were considered capable of “womanly arts” like weaving and crafts.

A Place in the Sun places the spotlight squarely on ten seminal women artists who represented the early, crucial eras of feminist expression — when giving artistic expression to the female experience was a novel thing. Selective and revisionist exhibitions like A Place in the Sun play an important role in a larger battle — the battle to correct sexist art historical narratives. But does that qualify women as a category for curatorial scrutiny? Especially in 2023, when, even though it is still a male-dominated world, a diverse array of women artists are a part of group shows, gallery programming, auctions and art fairs? In any curatorial practice, as in life, men aren’t ever a category. This show, however, was a wonderful surprise because of its focussed curatorial vision: A prism through which early feminism in India comes to light.

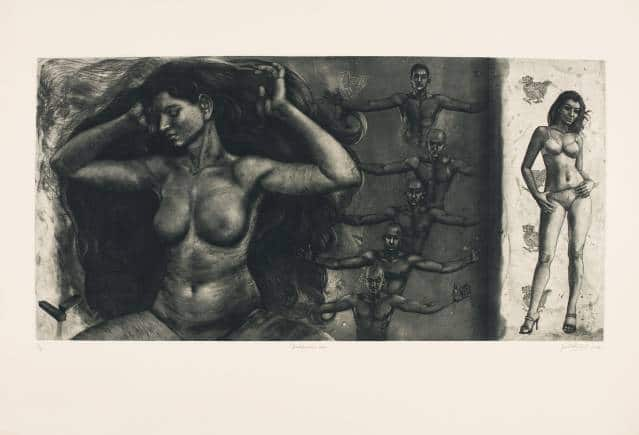

Much of my scepticism about the outdated “women-only” idea behind it vanished when I saw the works. I would still refer to it as a show of artists born between 1940 and 1960. There is much that these women share conceptually. The primary stimuli for all of them are personal moments and social currents around them that shaped their feminist impulses. Take Draupadi’s Vow, etching and aquatint on paper by Anupam Sud, 79, considered one of the finest printmakers of India. Once saved of being stripped of her clothes by Lord Krishna, Draupadi vows to keep her hair untied till her humiliation is avenged. Sad takes this episode from the Mahabharat and creates a detailed, layered work of temporal demarcation — a trope she has often used in her works to present dichotomous realities or perceptions. Dominating the canvas is Draupadi with her untied hair; in the background are her five defeated husbands.

Draupadi's Vow (2006), etching and aquatint on paper, by Anupam Sud.

Draupadi's Vow (2006), etching and aquatint on paper, by Anupam Sud.

On the right of the canvas is a woman of today, a contrast to Draupadi, in bikini and stilettos. She oozes a confident body image; almost model-like, daring the viewer to make something of her body. Sud says it is a work that draws from one of her earliest memories as a little girl: “I must have been a school-going girl. My mother told me that Draupadi lets her long hair loose as a vow. All women at that time had long hair. It was a beautiful image for me, especially because my mother told me Draupadi vowed not to tie her hair until her wish was fulfilled. It was a romantic image in my head, and it stayed with me.”

Untitled charcoal on paper (1960) by Devyani Krishna.

Untitled charcoal on paper (1960) by Devyani Krishna.

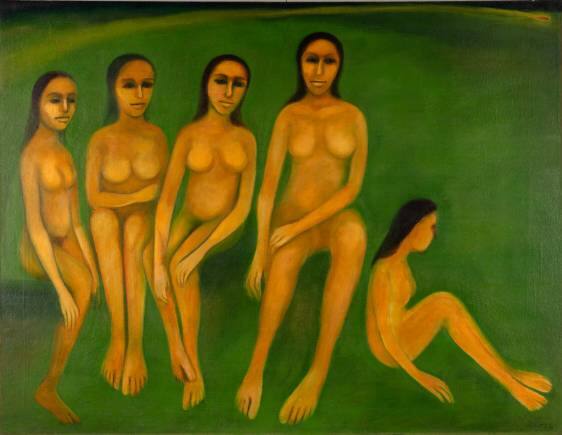

The show has works by Devyani Krishna, who legendary art critic Richard Bartholomew described as “India’s first woman artist”; and there is Gogi Saroj Pal, 78, whose untitled work of oil on canvas represents how she has used the female form in her works — victims in patriarchal structures; with limp limbs, tilted heads and dangly arms. Latika Katt, 75, who was once a lone girl in the all-boys Doon School, is a sculptor with naturalist leanings.

Artist Madhvi Parekh.

Artist Madhvi Parekh.

The 81-year-old Madhavi Parekh uses traditional crafts and art forms and juxtaposes them with her own fantastical and bulbous figures; Zarina Hashmi, who died in 2020 at the age of 83, is known for her meditative art of geometric and abstract forms, like Shobha Broota, 80, who also pictoralises elements of Indian classical music to meditative effect. Mrinalini Mukherjee’s tactile sculptures using knotted hemp ropes in glowing earthy hues is more today with its earth-loving, sustainable process of art-making.

'December 15th 2000' (2008), duco paint on fibreglass with vulcanized rubber tube, by Navjot.

'December 15th 2000' (2008), duco paint on fibreglass with vulcanized rubber tube, by Navjot.

One of the most stunning works in the show is a fiery red sculpture by Navjot, 74. Titled December 15th, 2000 (2008), made with duco paint on fibreglass and a vulcanised rubber tube, it is a woman in almost-foetal position — reiterating the concept of the underdog, particularly in the context of gender and sexuality. Is the woman in prayer, or intently in the middle of a wellness exercise, or is she simply protecting herself from the world? The tribal craftsmanship of Bastar, where Navjot spends much of her time, inspires a lot of her art. Traditional female crafts like weaving gets new meaning in her contemporary style, and mythological fertility figures and female divinities get gleefully subverted.

The youngest artist in the show is The River of Dreams (1994) by Rekha Rowdittiya, 64. Rodwittiya says It is an abstract, magi-realist work of oil and acrylic on canvas — robustly magnifying the everyday life of women in a hyper-coloured scheme. The artist says, “The River of Dreams is a work that speaks of violence, subjugation and oppression that women face, yet where hope continues to bolster the courage of women, not to allow their spirit to be crushed. The content in all my work is culled from the everyday life of women. It is through the lives of ordinary women from both rural and urban existence, that we today have a proud genealogy of feminist history.”

India’s first woman artist, Sunayani Devi, picked up a paintbrush in 1905 when she was 30 even as she supervised her kitchen. Self-taught, she had enough talent to attract the attention of Stella Kramrisch who organised an exhibition of her paintings in Germany in 1927. Devayani Krishna, whose maze-like drawing of charcoal on paper is one of the most intricate works in the show was born five years after Sunayani Devi began painting; Amrita Sher-Gil already had a career in Paris by the time India’s first art school-trained woman artist, Ambika Dhurandhar, earned her diploma in Bombay. B Prabha followed next, her work reflecting the realities of the marginalised in a piquant language. By the time Nasreen Mohamedi and Zarina Hashmi, both born a decade before Independence, established their careers, women were joining art schools in greater numbers, validating their practice not on the basis of their gender but on its context.

Artist Gogi Saroj Pal.

Artist Gogi Saroj Pal.

A Place in the Sun is the kind of show which is, on one hand, a historical gaze on Indian feminism. It is also a telling reemphasis of the female gaze in art. As Gogi Saroj Pal tells me, “Between all the artists present at the show, we got to see different point of views. Some use abstraction to showcase a version of the gaze, others like I use a figurative language to loudly voice our opinions on this gaze. The body is used differently by different people — it is the marriage of aesthetics, personal philosophy and the culture we’re situated within. All of this shapes our perception of ‘gaze’: things we fight for, and which, in turn, keeps our civilisation alive.”

Untitled oil on canvas (1986) by Gogi Saroj Pal.

Untitled oil on canvas (1986) by Gogi Saroj Pal.

A Place in the Sun: Women Artists From 20th Century India, at DAG, Taj Mahal Hotel, Colaba, until 21 October.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!