The recent clashes surrounding the recruitment process of Indian Railways paints a dire picture of India’s employment shortage, which wasn’t healthy to begin with. The vacancies to application ratio is a mind-boggling 1:25 if news reports are to be believed. What makes it worse is that not all of these vacancies are for high-paying jobs. The Indian economy has not been able to generate enough jobs to keep its fast-growing young population gainfully occupied for many years now. How deep is this jobs distress, especially after the pandemic? Four charts tell part of the story here:

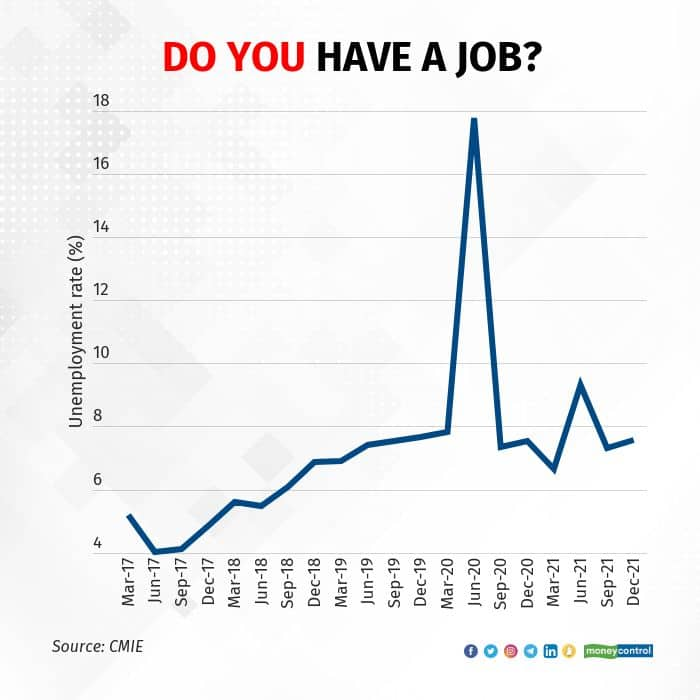

The bad, the ugly, and the pandemicIndia’s unemployment rate was on the rise even before the pandemic, from about 5 percent in FY17 to nearly 8 percent in FY20. A slowing economy has not been able to generate enough employment for its ever-rising young population. COVID-19 pushed millions out of jobs, adding to the distress.

The unemployment rate as measured by a private survey from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) surged due to the total lockdown triggered by the pandemic in April and May. But as restrictions were lifted, many have got back their jobs. Even so, the unemployment rate has begun inching up off late. With the third wave, it is likely that employment generation would slow down again.

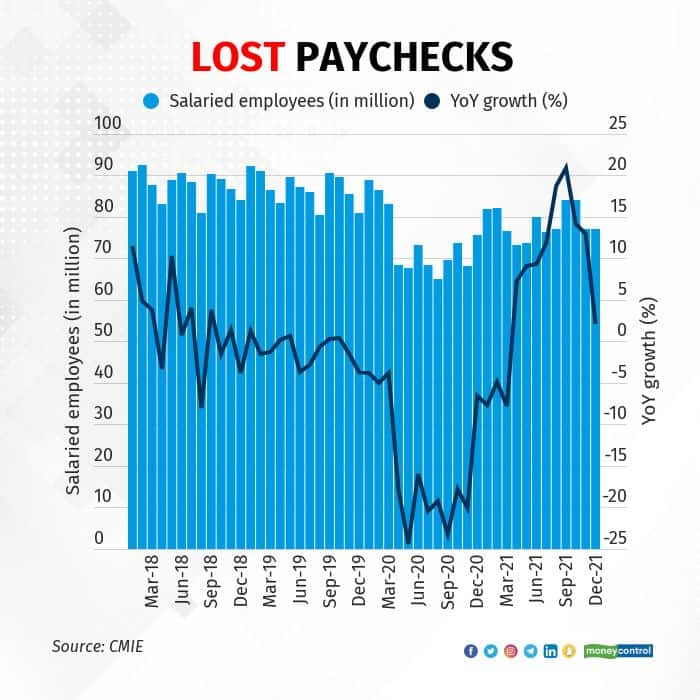

A lion’s share of employment generation in India is in the informal sector. Even as jobs have been lost, there has been greater formalisation of the economy with big companies gaining more market share and pushing out small firms. We should note that jobs in the formal economy are better paying with more security. The distress in the aftermath of the pandemic has been stark because of the loss of salaried jobs. While salaried jobs had picked up, the third wave has hit them again. In December, 9.5 million salaried jobs were lost while employment among daily wage earners and farmers went up. A drop in high paying and high skilled employment portends to weak consumption demand.

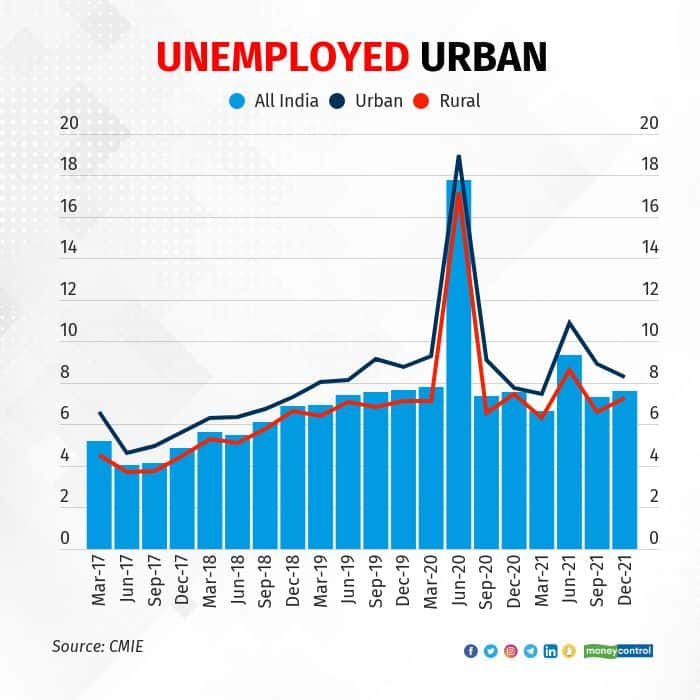

Since urban India generates the most jobs, it also lost the most in the aftermath of the pandemic. That said, the second and the third waves have hurt urban employment more than rural. Again, urban jobs are better in quality and remuneration compared with rural employment opportunities. The government’s flagship employment scheme Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MNREGS) ensures job creation in villages. However, in the absence of a similar support for urban citizens, weaker urban employment prospects pinch consumption harder.

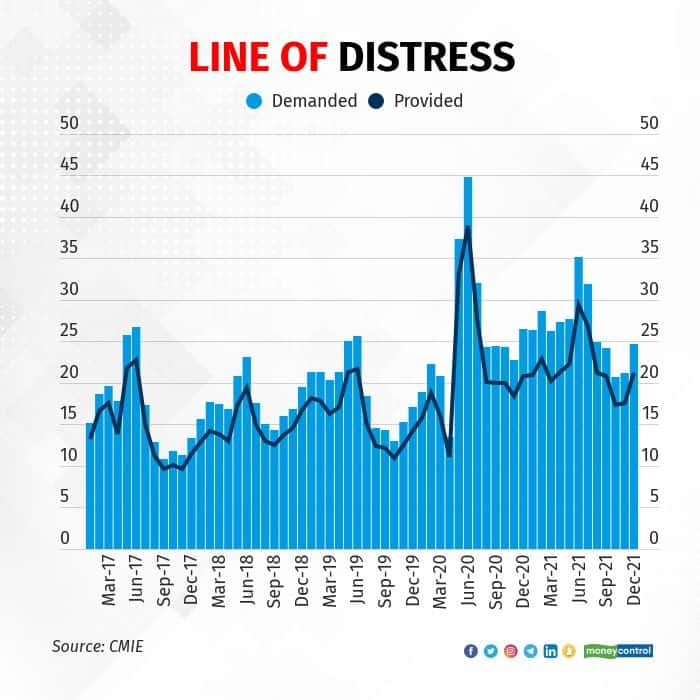

The demands for employment under the MNREGS have remained elevated ever since the pandemic hit. More than 24 million households demanded work in December, up from 21 million in November. Even as economists have asked for a separate scheme for urban centres, there are demands to boost the allocation for rural employment. As such, demands for work that surged immediately after the initial national lockdown, have not tapered off. This indicates that not all individuals out of jobs have found work.

An urban employment guarantee scheme, more allocation towards the existing rural employment scheme or even a renewed focus on construction and infrastructure would benefit the jobs market. India needs consumers to lift its economy. But for that, it needs to give a greater opportunity to earn to its citizens.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!