Earlier this week, West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee met Prime Minister Narendra Modi and asked for New Delhi to release pending funds to the state. According to Banerjee, the Centre owes over Rs 1 lakh crore funding to West Bengal for centrally sponsored schemes and money related to natural disaster claims.

For instance, the Union government has not given funds to West Bengal under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme since March 2022. This, the Centre has said, is because the state has not complied with its directions to implement the scheme transparently, once again putting the spotlight on the fractious relationship between the Centre and the state over finances.

Falling control over own finances?

First things first: expenditure by states is greater than the Centre's. Take the current year, where the Centre is budgeted to spend Rs 45.03 lakh crore and states collectively have a spending target of Rs 50.22 lakh crore. The states' budgeted capital expenditure, at Rs 8.85 lakh crore for 2023-24, is higher than the Centre's Rs 8.37 lakh crore, after adjusting for the loans component of its capex.

Also Read: India must lower fiscal deficit 'a lot more' to get higher rating, says S&P

Second, spending by states is known to have a greater impact on the economy. As per a 2013 paper by RBI economists, a 1 percent increase in revenue expenditure by states is estimated to result in a 0.6 percent increase in GDP, while a similar increase by the Centre raises the GDP by about 0.2 percent. The size of these 'multipliers' is even larger when it comes to capex: 2.1 for states and 0.4 for the Centre.

The problem, however, lies in the dynamics of states' revenue and expenditure. On the expenditure side, states are competing with each other to improve their infrastructure base so that they can attract private and overseas investments and create jobs. In this, the Centre has even offered its assistance by starting a scheme under which it provides long-term, interest-free loans to states for capex. The allocation for this scheme was increased by 30 percent in 2023-24 to Rs 1.3 lakh crore.

On the other hand, states have alleged the control they have over their own revenues has been reducing, with the rollout of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) in July 2017 further lowering their ability to tinker with tax rates and increase revenues.

That indirect tax revenue under GST is rising, even for states, cannot be denied. But the growth in GST revenue has not been uniform. Following the end of the GST compensation period in June 2022, certain states—especially mineral-rich ones such as Chhattisgarh—have felt the brunt of the new indirect tax regime being a destination-based system. And the government has admitted as much.

"I don't see how we can come up with something specifically targeted at them (states disadvantaged by GST being destination-based) – unless the Finance Commission looks at it and changes the devolution formula and gives them something additional," Vivek Johri, former chairman of the Central Board of Indirect Taxes & Customs, had told Moneycontrol in July.

The feeling of reduced control on their own tax revenue is also why states are widely considered to be opposed to the inclusion of fuel products such as petrol and diesel under GST. But this is a double-edged sword, with the Union government repeatedly calling on them to cut local taxes on petrol and diesel to bring down pump prices.

Own revenues and borrowings

Contrary to the above, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) pointed out in its recently published study of state finances that states' own tax revenue as a percentage of their overall tax revenue has gone up in recent years to 65.4 percent on average from 62.8 percent just prior to the rollout of GST, indicating that states' dependence on tax devolution from the Centre has reduced slightly since GST was introduced.

Sources of tax revenue that states still control, apart from fuel, include stamp duty, land registration fees, excise duty on liquor, and motor vehicle tax.

Also Read: Post GST compensation, states fall back on land and liquor to shore up revenues

States that have seen the largest increase in the share of their own tax revenue in overall tax revenue after the introduction of GST include Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, and Odisha. Meanwhile, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Punjab, Goa, and Gujarat have seen their own tax revenue form a smaller portion of their overall tax revenue.

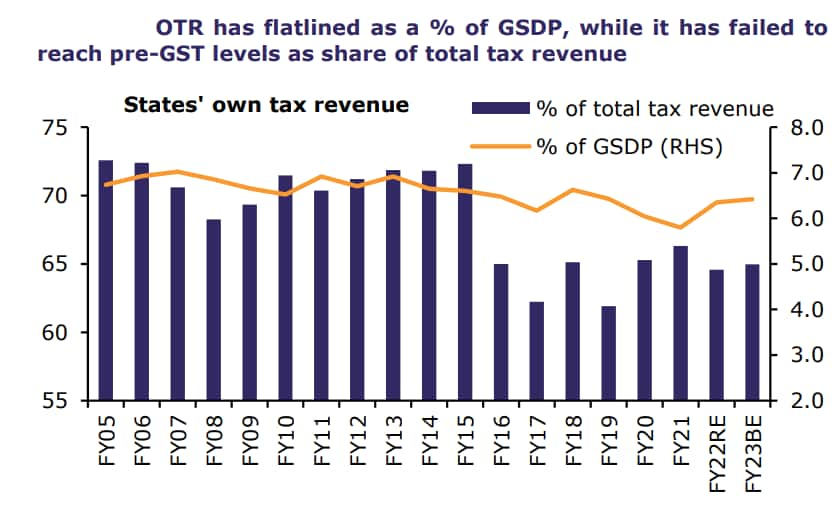

"However, while the RBI report claims that states' reliance on devolution from the Centre has decreased post-GST, a comparison with a longer period pre-GST shows that this is not the case," economists Madhavi Arora and Harshal Patel of Emkay Global Financial Services noted.

Source: Emkay Global Financial Services

Source: Emkay Global Financial Services

According to Arora and Patel, states' own tax revenue "has flat-lined as a percentage of GSDP (gross state domestic product), while it has failed to reach pre-GST levels as a share of total tax revenue".

The RBI report also said states have plenty of scope to increase their non-tax revenue by regularly revising charges on public services such as electricity and water and royalties from mining, among others. But the first of these is next to impossible for any political party that wants to return to power at the legislative assembly level.

If revenue does not rise to meet new expenditure, governments can always increase their borrowing from the market. Well, at least the Centre can, as it did during the COVID-19 pandemic. States, however, cannot borrow and spend freely as their borrowing limit is capped by the government, with their fiscal deficit threshold kept at 3 percent of GDP. Meanwhile, the Centre is still nowhere close to bringing its own deficit down to 3 percent, something that was to be achieved in 2006-07.

Also Read: Moving the goalposts — fiscal deficit target and a 20-year delay

The Union government is targeting a fiscal deficit of 5.9 percent for 2023-24 on its way to reducing it to 4.5 percent by 2025-26, as per the revised fiscal consolidation roadmap.

That states' borrowing limit is a sticking point can be gleaned from the fact that the finance minister has already been asked seven questions on the issue in the ongoing Winter Session of Parliament by MPs such as NK Premachandran and John Brittas.

Cesses and surcharges

In addition to an unlimited borrowing capacity, which, of course, must be used judiciously, the central government also has access to a pool of resources that it does not have to share with states: cesses and surcharges. And this pool has grown sharply in recent years, much to the consternation of states.

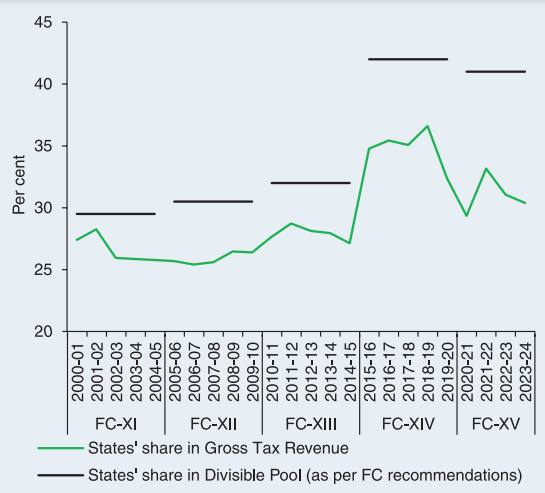

Currently, states get 41 percent of the shareable Union taxes, down from the 42 percent recommended by the 14th Finance Commission following the division of the state of Jammu and Kashmir into two Union Territories. This, for 2023-24, amounts to Rs 10.21 lakh crore that must be transferred to states this year, with the finance ministry on December 22 saying it had released an additional instalment of Rs 72,961 crore as tax devolution following a similar transfer earlier this month on December 11.

However, cesses and surcharges—such as the Agriculture Infrastructure and Development Cess, Road and Infrastructure Cess, and Health and Education Cess—are not part of this divisible pool of resources and are for the exclusive use of the Centre. And this pile of money has grown rapidly to 17.7 percent of the Centre's gross tax revenue in 2021-22 from just 6.4 percent in 2011-12.

The net result of the proliferation of the Centre's cesses and surcharges is that the actual tax devolution to states has been lower than what successive Finance Commissions have recommended.

Source: Reserve Bank of India

Source: Reserve Bank of India

As per the aforementioned RBI report, the pool of Union taxes to be divided among states has fallen to 78.9 percent of gross tax revenue in 2021-22 from 88.6 percent in 2011-12. This is despite the 14th Finance Commission recommending an increase in the tax devolution to 42 percent from 32 percent, effective April 2015.

If India is to become a developed country by 2047, all levels of government need to work together. And as the name suggests, co-operative federalism requires some give and take; the Centre will have to address valid concerns of the states, which must become more efficient and find new sources of revenue.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!