Until May 2020, the Indian food-delivery startup Zomato’s fortunes seemed firmly tied to the purse strings of China’s Alibaba Group Holding — its largest investor owning nearly a third of the company via investment arm Ant Financial. Alibaba also had the required heft to lead the unicorn’s future funding rounds. No other single large influential investor was seen on the horizon.

But what a difference a few months can make!

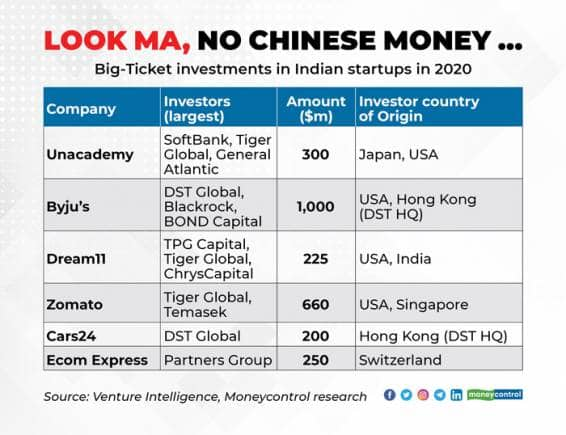

Since May, Zomato has raised $660 million from non-Alibaba investors, including Tiger Global Management, sovereign wealth fund Temasek, Fidelity and Mirae. As Zomato’s fortunes have delinked from that of Alibaba, so have the rest of India’s. The government’s ban on Chinese investments in April last year after the border conflict was expected to jolt the startup ecosystem because of the perceived dependence on Chinese investments by Indian startups.

Eight months on, the reality is starkly - and pleasantly - different.

Since the ban, Indian startups have raised $6.6 billion across 438 rounds - from Seed to Series F and beyond; and from early stage ventures to established unicorns, according to data from Venture Intelligence. This is something that was really not expected - and certainly no one thought it would all go so smoothly.

“The earlier buzz created around Chinese investments was a bit unnecessary. China has been overplayed in India from a financial standpoint,” said an investment banker who works on large internet deals, requesting anonymity.

“The dent has not been felt because Japanese, Korean and other investors have filled in. Tencent is perhaps the only dent felt because they were consistently writing cheques of $50 million and more,” the person added.

Even before the ban, the startup investment landscape in India was dominated by Japan’s SoftBank, South Africa’s Prosus (Naspers), Tiger Global and others, but Chinese investors did have a distinct place. Alibaba for instance held (and holds) serious stakes in Snapdeal, Paytm, Zomato and BigBasket; Tencent in Dream11, Byju’s, Udaan and Swiggy- all among the country’s biggest startups, and most influential at some point. But these and other large firms have easily found other sources of capital – the result of global liquidity where public and private market investors are more exuberant than ever.

“The funding gap from China has been filled by other investors - private equity, hedge funds and strategies. There is a flood of global liquidity and all asset classes are benefitting,” said Ashish Sharma, CEO of Temasek-owned InnoVen Capital India, which provides debt to startups.

Chinese investors such as Shunwei, CDH and Morningside Ventures, were active in Series A and B rounds as well. Newer non-Chinese investors including Korea’s KB Global and Korea Investment Partners (KIP), Alpha Wave Incubation and many others have filled this void.

From May, investors poured $613 million into 265 seed and Series A deals with both deal volume and value similar to previous years -- significant given the Covid-19 pandemic and the Chinese investments ban.

“Some Chinese investors invest $5-10 million in a startup, but neither do they lead the round - convince other investors or put the largest amount, nor do they decide the valuation. These investors have been the easiest to replace because there is a lot of capital available,” said the banker cited above.

With more than a dozen dedicated early-stage funds in India, and overseas firms cutting cheques now and then, there is arguably a glut in early-stage funding.

“In the early stage there is $5-6 billion of dry powder (uninvested capital), so I don’t expect any meaningful impact from the absence of Chinese investors. In some oversubscribed funding rounds, Chinese investors are also being given an option to reduce their stake through secondaries, particularly in companies where they have a large stake,” Sharma said.

Even for large deals of $100 million and more, and in pre-IPO rounds at some firms, new investors have shown interest. T Rowe Price, Blackrock, DST Global and Fidelity have all either started selectively looking at Indian startups, or increased their presence in the last few months.

Immediately after the ban, many startups had to reconfigure funding plans and look at different options overnight, but founders acknowledge that the transition has been far smoother than expected. “It (having a Chinese investor) is something you mention in passing, not even a key topic anymore at board meetings,” said a founder who has a Chinese investor, and did not want to be named.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!