With both the RBI and the Government having done the expected, it now remains to be seen if the economy will do what is expected of it. The Government gave sops for consumption through a large tax bounty in the Budget and then looked to the RBI doing the same for investment by lowering policy rates. The RBI obliged with a 25 bp rate cut, which may not be large but must be seen as intent and perhaps indicative of further reductions.

The last time it cut policy rates was in 2019-20, under similar circumstances when Q4 GDP fell off. It reduced rates by 185 basis points (bp) between April 2019 and March 2020, made easier by benign inflation which stayed within bounds.

Reprioritising economic growth

Currently, inflation is easing but still beyond RBI’s target, which explained its hesitancy to bring down rates. But the 5.4 percent GDP growth in Q2 FY25 changed everything, as recession worries overtook inflation fears. The pressure to cut rates came in many ways, from debunking monetary policy’s utility in controlling food prices to complaining about high lending rates inhibiting credit offtake. In fairness, the RBI had always been maintaining that its rate signals were targeted more at inflationary expectations than inflation itself. But with a new Governor and changes in composition of monetary policy committee (MPC), it was inevitable that the RBI would soon act, especially after the Budget made pro-growth moves.

Both the narratives, namely, tax bounties spurring consumption and rate reduction boosting private investment are not new but a reality check is always good.

Leads and lags in monetary transmission

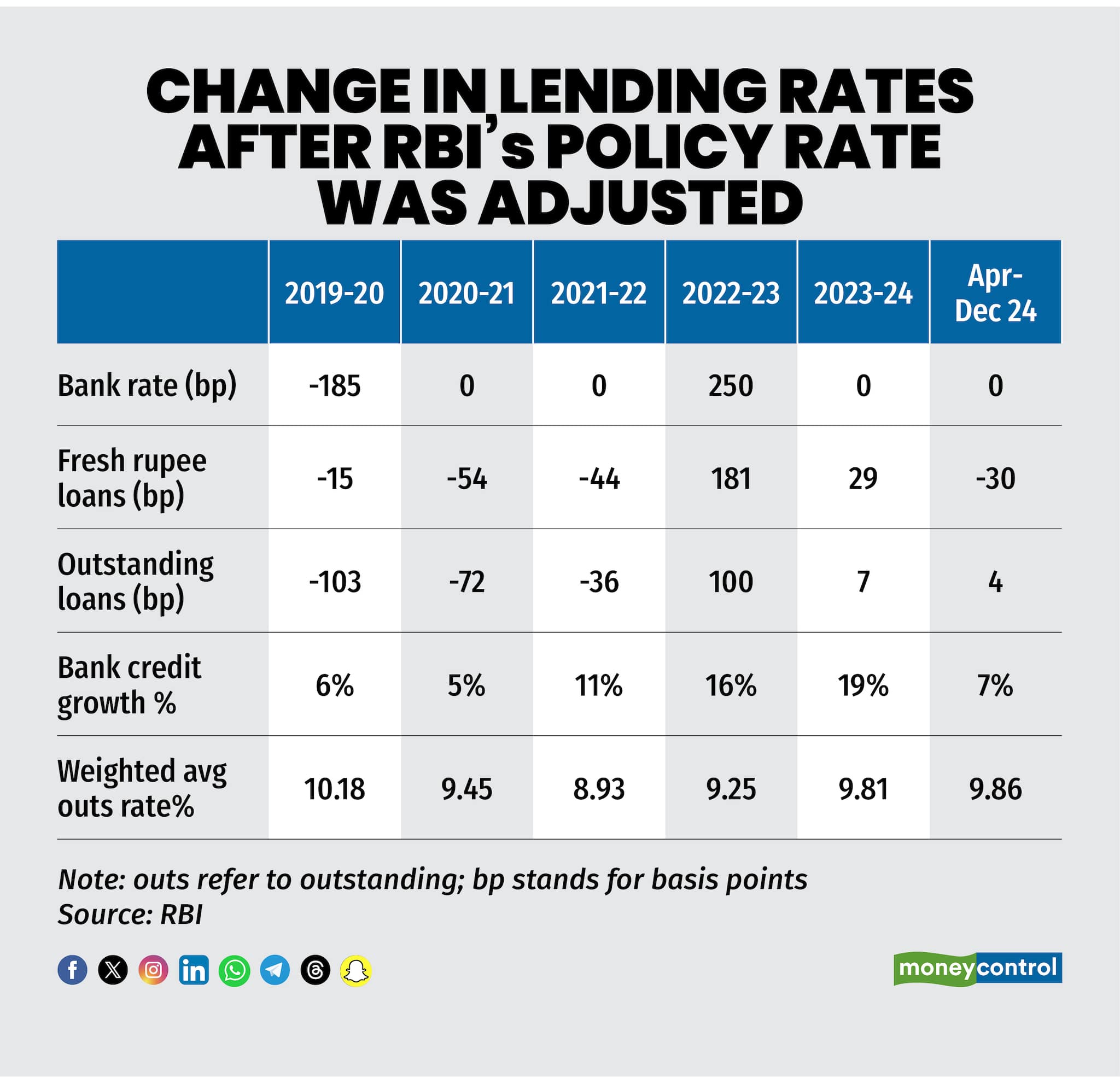

Monetary policy works through the transmission mechanism which has traditionally been weak and slow for many reasons. In a bank-led financial system, transmission has to work through credit channels as other asset markets were either not well developed or integrated. Data on policy rates, lending rates and credit growth for past years show some interesting trends.

The 185 bp policy rate cut in 2019-20 led to a 113 bp drop-in incremental lending rates, over three years. But weighted average outstanding rates reduced immediately by 103 points in the same year. Likewise, the 250 bp rate hike from May 2022 percolated over two years and only partially; again, weighted outstanding loan rates rose by 100 bp in the same year. This was because nearly half of all bank credit is working capital or other credit linked to floating rates, where new rates apply instantaneously. The reduction in fresh lending rates, which is relevant for credit growth, was much lower and spread out.

Also, credit growth seemed to be at odds with lending rate changes. When bank rates fell during 2019-20, bank credit growth was tepid at 6 percent and 5 percent in the two years, although we must also consider the pandemic effects. And when rates were increased by a hefty 250 bp in May 2022, contrary to expectations, credit grew by a massive 16 percent and 19 percent during 2022-23 and 2023-24.

Even factoring in leads and lags the growth seems inexplicable especially in rate sensitive sectors such as personal loans. Growth was limited to personal loans and the NBFC segments with industrial credit continuing to lag. Home loans, unsecured lending, gold loans and credit card debt seemed impervious to rising costs and it took the intervention of the RBI to moderate growth. The reluctance of industry has been a feature of both low cost and high-cost regimes indicating that other factors, such as excess capacities, poor demand or the ease of doing business, were at work.

Consumption growth, not cheaper credit, is likely to trigger investment

As for the tax bounty to the middle class impacting urban consumption, it is difficult to quantify its effect given the large income inequality and the nature of consumption. Even though over 80 percent of tax filers fall under the Rs 12 lakh income bracket, income distribution is skewed with a third having incomes below Rs 5 lakh and nearly half in the Rs 5 lakh-Rs 10 lakh bracket. The composition of personal consumption expenditure also shows nearly 40 percent on essentials (food and other non-durables), about 50 percent on services (mainly transportation, housing and miscellaneous services) with consumer durables only about 3 percent. Could cheaper bank credit help? Perhaps, but nearly half of personal bank credit is long-term home loans, whose impact on GDP is not through consumption but through gross capital formation. Maybe if the RBI were to unshackle personal loans and lending to NBFCs, there could be a consumption boost in conjunction with the tax reliefs. This may be the other agenda for the RBI and its moves will be crucial.

While bank credit’s linkages with growth work though both consumption and investment, it is the latter which is important for job creation and income growth. Cheaper credit alone may not do the trick though some segments such as MSMEs have been absorbing credit on the back of Government guarantees. Even if industry were to take the bait and invest, will the banks be ready? This is the other issue with bank credit, namely, their risk appetite and capability. It must be said that their cleaned-up balance sheets are in large part also a result of risk avoidance and write offs. It is not clear if they would want to take risks with project finance again. Even if they did, their capability is severely constrained by their unfavourable asset-liability profiles which are not conducive for long term lending, which is why over half of current bank credit to industry is working capital and medium-term loans. The only bet for private investment picking up seems to be a significant uptick in consumption more than cheaper credit and that remains to be seen.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.