When it rained in Delhi on May 4, the national capital almost erupted in celebration. Social media was flooded with memes and pictures disproportionately higher than the amount of rain the scorched city received in the middle of a once-in-a-century summer.

From the Himalayas to the northern plains and beyond, this year the summer has been unsparing with prolonged spells of record high temperatures reported from large parts of the country.

So when it rained on the evening of May 4, it was a welcome respite from a searing heatwave but for a Mukul Kumar, a cart-puller, it made little difference.

The spell of rain brought the mercury down a few notches but sent up humidity, causing immense discomfort.

“I have to ride around the city, delivering goods from one place to another. The rain has driven away the hot winds but now it has is sweaty and more tiring,” Kumar said, as he stopped his cart loaded with benches on the Delhi-Meerut Expressway to take a break and quench his thirst.

Their office is out in the sun

Kumar is among hundreds of thousands of people in Delhi—and millions across the country—who don’t have the luxury of an office or work from home.

Their workplace is out in the open—heat-reflecting asphalt roads, pavements or a tree, which offers some protection from an angry sun.

Cart and rickshaw-pullers, auto drivers, street vendors, delivery personnel, construction workers, farmers and traffic cops are among a long list of people who have to be out in the open to earn a living, whatever the weather.

For people like Mukul Kumar, who transports goods on a cycle cart, a brief stop for rest and a few sips of water is the best way to beat the heat.

For people like Mukul Kumar, who transports goods on a cycle cart, a brief stop for rest and a few sips of water is the best way to beat the heat.

Imran Ali sells cold water and lemonade on his pushcart that he has set up near the Ghazipur flower market. He has made peace with the heat. Heatwaves and alerts were for the well-to-do and those who lived and worked in air-conditioned places, he said.

“I don’t understand degrees and Celsius. Yes, summer started early this year, that’s all I understand,” Ali said in a matter-of-fact tone. “But then I can’t stop working because I have to feed my family.”

Also read: India's heatwaves are testing the limits of human survival

Scorching April

As the summer gobbled up the few weeks of spring that usually follow winter, a severe heatwave swept through large swathes of India in April.

This April was the third hottest in 122 years, the last was in 1901, the India Meteorological Department (IMD) has said.

In parts of north, northwest and central India temperatures soared up to 46 degrees Celsius. The average maximum temperature in April was 35.3 degrees Celsius, 1.36 degrees above normal.

A vendor covers vegetables with a sheet and wet jute bags to protect them from the sun.

A vendor covers vegetables with a sheet and wet jute bags to protect them from the sun.

Livelihoods on line

The heat is also affecting livelihood, with small businesses particularly hard hit. Vegetable, fish and flower sellers are having a hard time keeping their wares fresh.

“We can’t stock a lot of veggies as they are anyway perishable but this heat has made it worse. Customers don’t buy withered vegetables or fruits,” said Anil Pandey, a vegetable and fruit vendor in neighbouring Ghaziabad.

To beat the heat, vendors cover their carts with wet jute bags and blankets to protect the vegetables from the blazing heat that sucks the moisture out.

The quantity of vegetables and fruits that go waste or decay in summer is usually high, reducing their profits, but this year, it is worse.

“Our income anyway goes down these few months but this year, we hardly had any spring and the heat came right after Holi,” Pandey said.

Also read: India, Pakistan must brace for even worse heatwaves

Satyadev Prasad Gupta, a former chairman of the Agricultural Produce Market Committee (APMC), Ghazipur, said the supply of fresh vegetables to the market had come down because the intense heat had affected crops.

“We can keep potato and onion produce in cold storage for a limited time but fresh vegetables are sold daily basis,” Gupta said.

Nitesh Yadav knows it all too well. Instead of vegetables, this summer he is selling dahi-bhallas (fried lentil dumplings served with yogurt and sweet and sour sauces).

It is summer and dahi-bhalla and nimbu-shekanjee (lemonade) are in demand. Lemon is costly and so I thought bhalla is better. Storing vegetables was a problem anyway,” Yadav said. Many like him have shifted to this seasonal business.

Nitesh Yadav switched to selling dahi-bhallas from vegetables as they wilt in the heat, causing losses.

Nitesh Yadav switched to selling dahi-bhallas from vegetables as they wilt in the heat, causing losses.

At the Ghazipur wholesale fish market, which opens from 6 to 10 am six days a week, traders who usually display the fish on cemented platforms now move them to ice containers and deep freezers at around 8 am.

“The sun is very strong even at 8 am. We can’t afford to keep the fish on display for long. We keep one or two sample pieces for our customers,” said Mushtaq Ahmed, a fishmonger.

Small sellers who can’t afford deep freezers have cut down on their purchases to avoid losses, wholesalers told Moneycontrol.

Shifting hours and loss of business

Several street vendors this writer spoke to talked about losing business in the afternoon when temperatures are at their highest.

Many have shifted their business hours to mornings and evenings to avoid the heat and to keep pace with the customer flow.

“Fewer customers are coming in the peak afternoon hours and so I close early. I sell chole and kulche (bread and chickpeas), which I can’t keep for the next day. Income is down these days,” said Rajeev, who runs a food stall in Ghazibad's Indirapuram, which is 22 km from Delhi.

India lost 118.3 billion work hours—the highest for any country—in 2019 due to extreme heat, The Lancet Countdown report on health and climate change 2020 said. It translates to a loss of 111.2 work hours per person.

Rakesh Singh, who sells readymade garments in a street corner in Indirapuram, also starts late afternoon. “Hardly anyone comes during the day, so it is better to stay from the heat,” he said.

For auto drivers, too, the business is slow. Few people want to risk their health in this heat.

“I keep on drinking water and park my auto underneath flyovers or in the shade to stay safe,” said Monu, an auto driver at Sarai Kale Khan, a transport hub in southeast Delhi.

On a recent afternoon, rows of autorickshaws were parked under a flyover, as drivers waited for customers.

“Since our vehicle is open, the hot winds cut through our skin and face. Customers also find it difficult to travel in such hot conditions and prefer cabs,” said auto driver Satendra Singh.

Parked under a flyover in Delhi to escape the heat, an auto driver takes a nap. Business is slow in the afternoon as the temperature peaks. (Images: Nilutpal Thakur)

Parked under a flyover in Delhi to escape the heat, an auto driver takes a nap. Business is slow in the afternoon as the temperature peaks. (Images: Nilutpal Thakur)

Global warming will increase work-related heat stress, damaging productivity and causing job and economic losses. Poorest countries would be the worst hit, the International Labour Organization (ILO) has said in a report.

By 2030, 2.2 percent of the total working hours worldwide would be lost because of high temperatures, a loss equivalent to 80 million full-time jobs, it said. It will cost the global economy $2,400 billion.

At the busy Bhairon Marg-Pragati Maidan intersection in central Delhi, three traffic police personnel were checking vehicles for papers. They had chosen a spot in a shade to do their work.

“This is the maximum we can do, apart from drinking lots of water and covering our faces. Ours is a field job and there is no escape,” one of them said, refusing to be named. “But we are not in this alone, there are so many others working hard,” the traffic cop said.

(Image: News18 Creative)

(Image: News18 Creative)

Business as usual

While some have shifted their work hours or found some shade to beat the heat, for construction workers and delivery personnel, there is no such escape.

Delivery executives, who have to deliver food or other items within a specified time, say there is no option when an order comes.

“Others can opt to deliver in the evenings or mornings, we have no choice. When an order comes, we have to be out no matter if it is hot or cold,” said Ajay Kumar, who works with a food aggregator.

Across Delhi and its suburbs, construction workers with their heads and faces covered with a piece of cloth to protect themselves as they plaster the walls or lay bricks are a common sight.

“We have to make a living. My brother works as a farmhand. I feel I am better off than him,” said a worker at a building site in Noida.

Earth on fire

A heatwave can cause dehydration, heat cramps, exhaustion or even heat stroke when people are exposed to high temperatures and the sun.

A heat stroke can raise body temperatures to 104°F and cause seizures or coma, the National Disaster Management Authority has said in its heatwave factsheet.

And then there is heat exhaustion which is marked by fatigue, weakness, dizziness, headache, nausea, vomiting, muscle cramps and sweating.

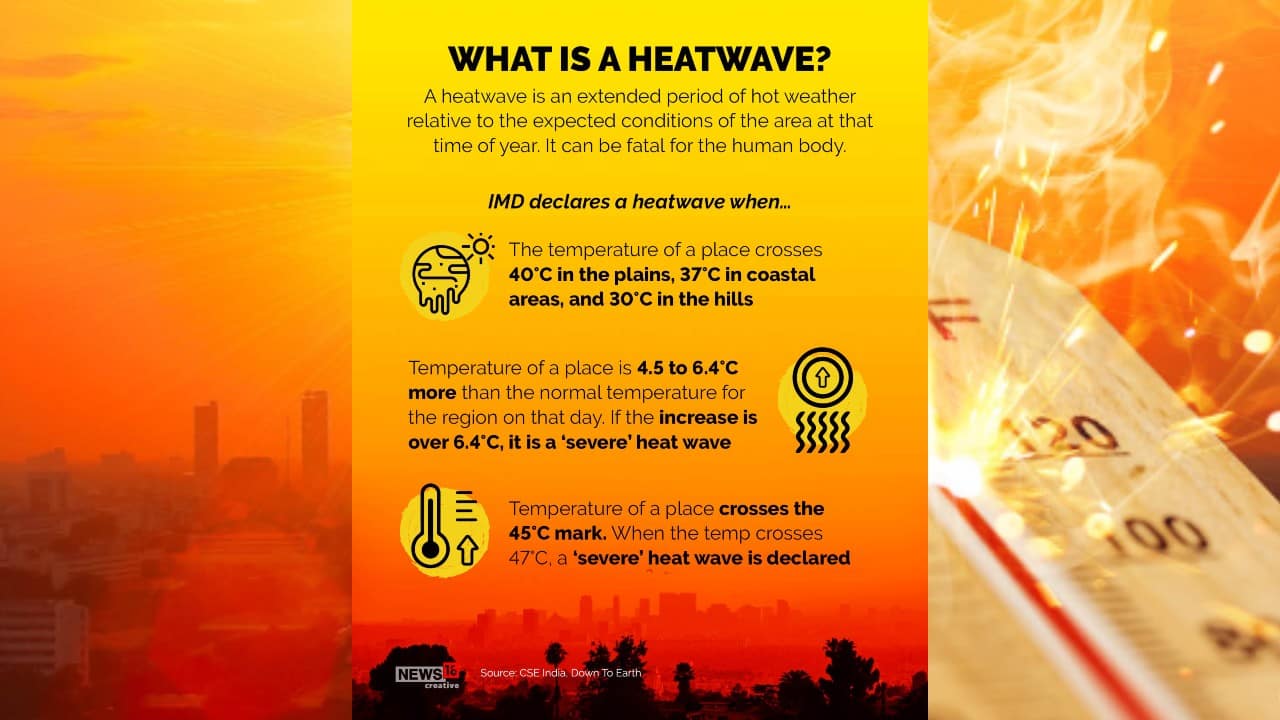

A heatwave is an extended period of hot weather relative to the expected conditions of the area at that time of year. It can be fatal for the human body. (Image: News18 Creative)

A heatwave is an extended period of hot weather relative to the expected conditions of the area at that time of year. It can be fatal for the human body. (Image: News18 Creative)

While the IMD said lack of rainfall was the immediate cause of the extreme weather, climate change experts point to global warming.

The United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has warned that India and other parts of South Asia are likely to face more frequent and intense heatwaves and extreme rain in the coming decades.

With the met department warning that heatwave conditions are set to return in some parts of the country over the next few days, it is going be a long summer for a large section of Indians.

“It’s so difficult. We stay out in the open all day long. We just hope the monsoon, and not just a few showers, come soon to give us some real respite,” said Mukul Kumar, as he wiped the sweat from his forehead, pushing ahead with his cart laden with benches.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!