As the US Federal Reserve attempts to undo its trillion-dollar pandemic-era excesses, it seems that it is trapped in a state of perpetual policy manipulation, alternating between stimulating and slowing down the economy to prevent an inflation spiral.

Quick recap

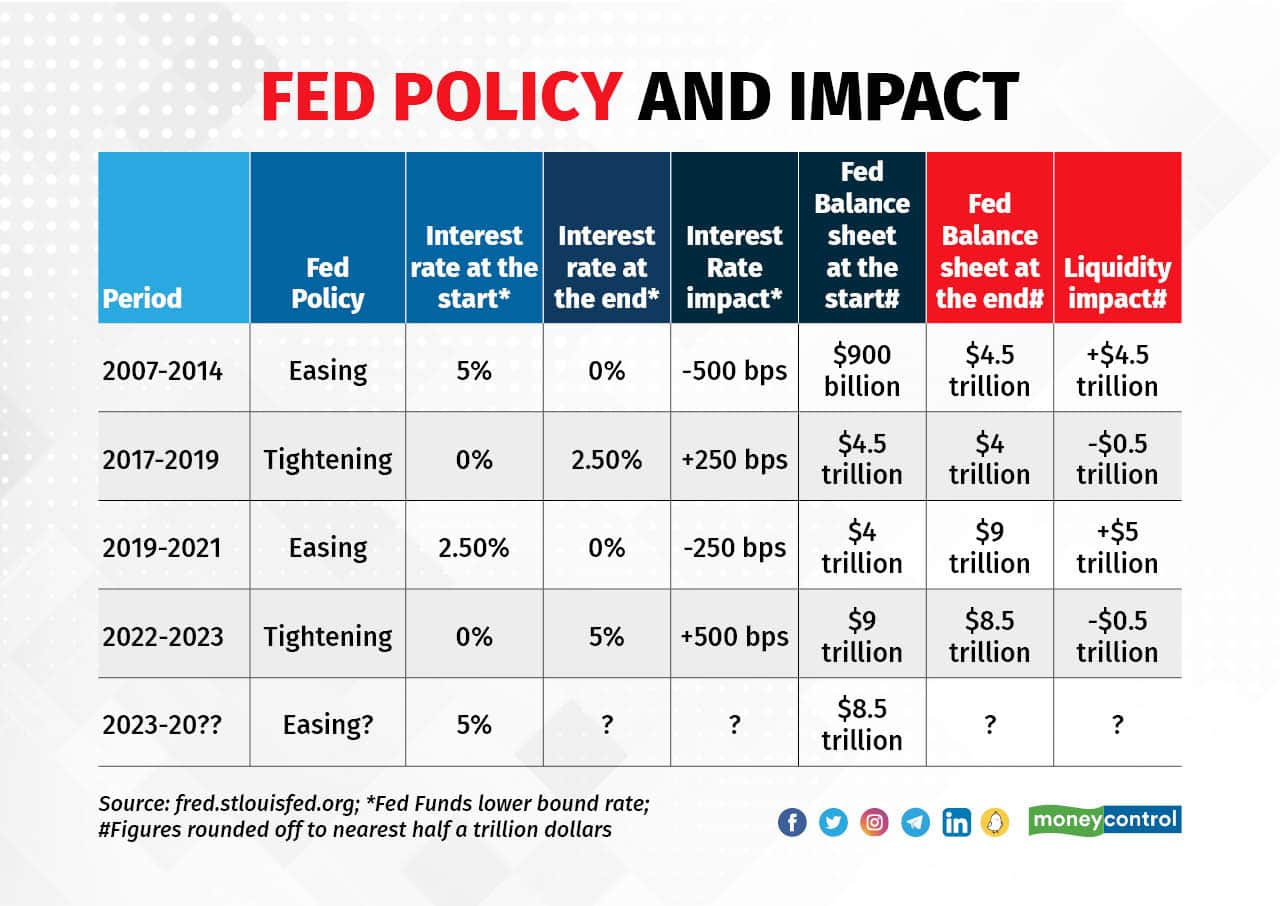

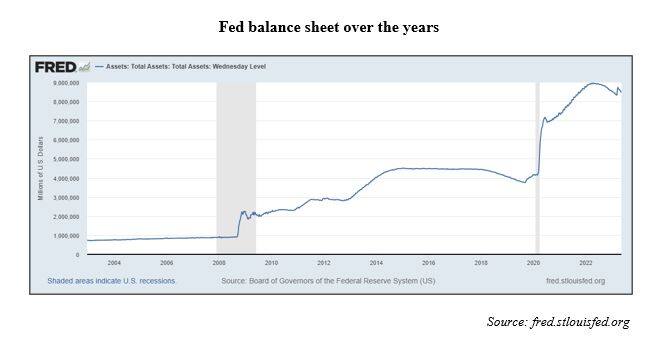

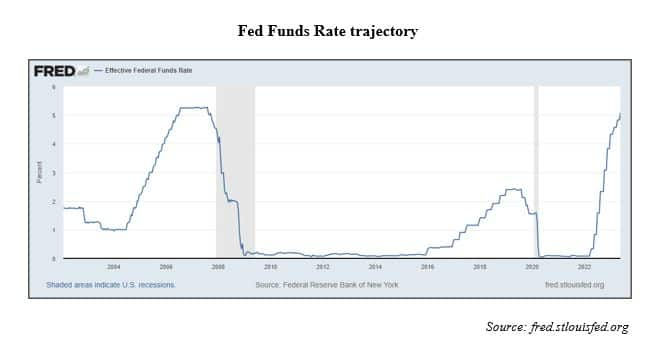

The US economy has continuously been supported by money printing or quantitative easing and near-zero interest rates ever since the financial crisis of 2008-09. It went through its first round of easing from 2009 to 2010, which had to be followed by another round in 2010-11 to stimulate the economy.

ALSO READ: Finmin's Rs 7-lakh relief to taxing foreign spends on credit cards can't resolve TCS crisis

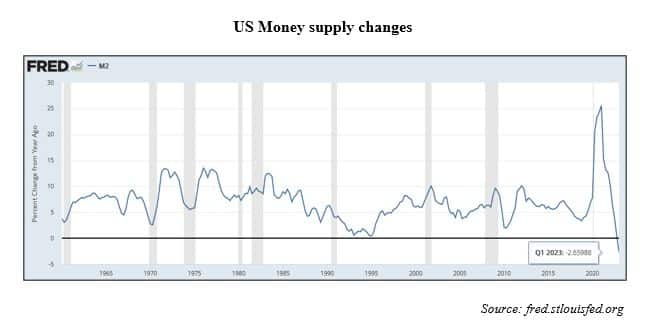

Growth of M2 money supply, a benchmark measure of cash and cash-like assets circulating in the US economy, doubled from about 5 percent to about 10 percent in these periods. Money supply, or the money in circulation in an economy, is majorly influenced by central bank actions. Money supply drives consumption and investment and thereby the economy’s trajectory.

Unwinding attempts

The programme was halted when, according to the Federal Reserve, economic conditions were improving. However, when the economy showed signs of weakness again, another round of stimulus was announced in 2012. Three rounds of pumping new money worth trillions of dollars were needed to support the economy. Money supply growth jumped back up to 10 percent levels.

ALSO READ: MC Explains | What to do with your Rs 2,000 currency notes?

Finally, in the second half of 2017, with an optimistic take on the current economic picture, the US central bank decided to taper its balance sheet and bring it back to normal. And thus began the massive process of quantitative tightening and increasing interest rates.

This attempt to normalise, however, didn’t last long. The world had barely witnessed a year of unwinding the excesses of 10 years by the Federal Reserve, before it decided to take a U-turn in January 2019 to “brace the slowing US economy.” Money supply growth shot up from about 3 percent levels to 7 percent by the end of the last quarter of 2019.

Stimulus spending

Then, along came the pandemic. The Federal Reserve pumped trillions of dollars into the US economy to help it deal with the economic restrictions imposed during Covid-19. Money supply witnessed double-digit growth for seven consecutive quarters till the end of 2021.

ALSO READ: Commissions to drop if SEBI’s proposal to cut MF expense ratio goes through, say distributors

The economy did bounce back with monetary and fiscal assistance, but inflation got out of hand. When money supply increased so much so fast, more money was chasing goods in the economy, which resulted in inflation.

The Fed thought the price increases were a result of pent-up demand and supply-side disruptions and thus transitory and stuck to its easy-money stance. Then, in early 2022, the Fed acknowledged that the inflation problem wasn’t transitory after all, but it was too late.

Inflation in the US had hit 40-year highs. Since then, the Fed has increased benchmark interest rates by 500 basis points from near zero in an effort to tame inflation. It also embarked on a balance sheet-reduction programme, trimming its assets of about $9 trillion by up to $95 billion each month.

Money supply growth in the US turned negative in 2023, a first since at least the 1960s, according to recently published Federal Reserve data. M2 money supply shrank by 2.7 percent year-on-year in the quarter ended March 2023. When money supply contracts, less money chases goods and prices tend to fall.

Cusp of policy U-turn?

This is the most aggressive monetary policy tightening by the Fed since the 1970s. And the Fed isn’t done. As recently as May 3, the Fed hiked rates by a quarter point to 5.0-5.25 percent, the highest level in 16 years.

ALSO READ: Five Sebi proposals may make mutual funds cheaper and more transparent

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) hinted at flexibility and opened the door to a pause. It stopped saying that “some additional policy firming may be appropriate” and instead said future interest rate decisions will be made on a meeting-by-meeting basis.

Jerome H Powell, chair of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, however, refrained from confirming a pause in rate hikes in June and dismissed rate cuts in 2023, given their view that it will take some time for inflation to come down. The FOMC also reaffirmed it will continue to trim its balance sheet according to plan.

Further complicating the money supply situation are the stresses plaguing the US banking sector, which are expected to weigh on credit offtake as banks become more conservative. Lower credit growth translates into lower consumption and investment activities.

This isn’t good news for the US economy. Signs of the economy slowing down are already becoming evident, with much of the effects from tightening yet to show up.

After almost halving headline inflation over the past year, the Federal Reserve is finding it tough to cool inflation further. There is a real possibility that the Fed will overdo its current tightening as it aims to bring headline inflation down to an arbitrary target of 2 percent.

This could stir up defaults, financial instability, asset price corrections and an economic recession. This, in turn, could trigger another sharp, sudden policy U-turn similar to past instances when there was market instability.

We can expect interest rate cuts and money supply expansion from the Fed to save the economy from this self-created downcycle and into the next cycle of high inflation.

Monetary cycles and gold

Gold rallied from 2008 to 2011 on the assumption that all the money-printing by central banks would lead to massive inflation. But that didn’t turn out to be the case, leading to a big correction in gold prices later.

The money printing, aka monetary inflation, didn’t result in price inflation then because the new money largely remained in financial circles. Banks used the bailout money to shore up their balance sheets. Given that the money didn’t trickle down to the real economy, price inflation was largely absent.

ALSO READ: Six ways to save your job in the current storm of layoffs

This time, money was given in the hands of people to cope with the economic effects of the pandemic, which resulted in real spending and hence was inflationary. Gold prices rallied as a result. Currently, with inflation looking entrenched and growth slowing, stagflationary conditions are ideal for gold.

Bet on gold

Gold, which tends to do well during economic downturns, market volatility and inflationary episodes, can be a good bet to diversify your portfolio against this mismanagement of economies and currencies, where central banks oscillate between extra-loose and extra-tight policymaking, disrupt sustained economic recoveries by disturbing natural economic cycles, and push the can down the road. Remember, history might not repeat itself, but it does rhyme.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!