The Union Budget for 2022-23 will be framed just before the elections to five states—Goa, Uttarakhand, Manipur, Punjab and Uttar Pradesh. Of these, the state of Uttar Pradesh is so important for the ruling party that Morgan Stanley, in their recent India equity strategy note, was moved to say, ‘The most important state election next year could be the one in Uttar Pradesh. A setback in that election could threaten policy momentum. As we have noted, government policy is major source of our optimism. At the minimum, an adverse election result will produce volatility.’ Given that these elections are so important, will not the Union Budget have one eye on them?

State of the economy

That said, the government’s finances on the eve of the Budget are in good shape. Tax revenues have been buoyant, partly the result of very high nominal GDP growth of 23.9 percent in the first half of the current fiscal year, but also because of better compliance and the increasing formalisation of the economy. RBI’s state of the economy report for the current month said, ‘revenue expenditure (less of interest payments and subsidies) of the general government (Centre plus 18 States) during November-March 2021-22 is expected to grow by 27 per cent, after accounting for expenditure proposals contained in the SDG-2 (Supplementary Demand for Grants) and assuming States will meet their budgeted targets. Similarly, capital expenditure is expected to grow by 54 per cent during November-March. The higher revenue expenditure growth, a proxy of government final consumption expenditure, is expected to support economic recovery, while robust capex could crowd in private investment and improve medium-term growth prospects.’

The economy has rebounded after the second covid wave and the government’s chief economic adviser has been talking of a V-shaped recovery. Many of the high frequency indicators show rapid growth. The RBI state of the economy report says, ‘Aggregate demand conditions point to sustained recovery, albeit, with some signs of sequential moderation.’

The corporate sector, the engine of growth, is in fine fettle. Balance sheets of both the corporate and banking sector are in much better shape than before the pandemic. The twin balance sheet problem is largely behind us, especially now that we have a ‘bad bank’. The same can be said of NBFCs and even, to some extent, of real estate balance sheets. Companies have raised huge amounts of cash from both the public and private markets. The long investment drought is poised to end.

Inflation

Surely, if the economic recovery has been gathering steam, the government will have some spare cash for pre-election sops for the masses?

The problem could be inflation, especially core inflation. Long term bond yields have moved up as the RBI tries to mop up liquidity---what some have called ‘stealth tightening’. The new Omicron variant of the virus threatens to throw supply chains out of kilter once again, raising the prospect of higher supply-side inflation.

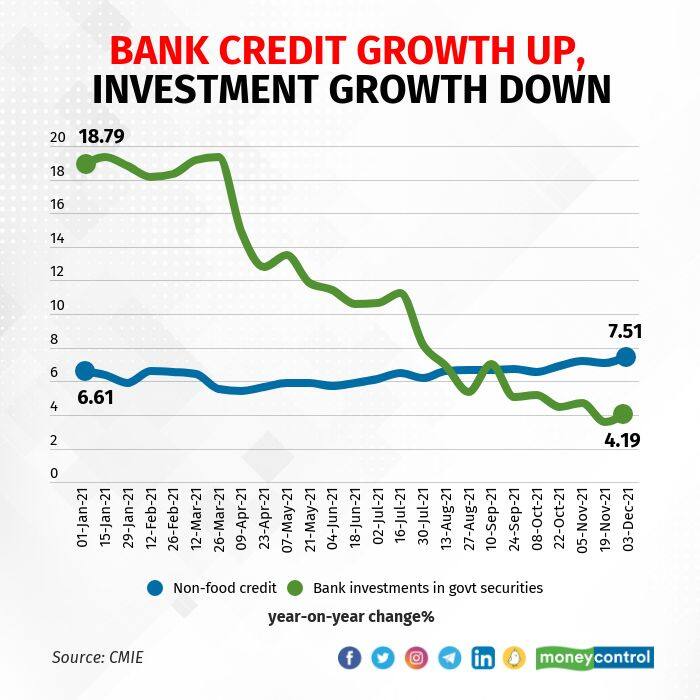

The accompanying chart shows how growth in banks’ investment in government securities petered out as growth in bank credit has improved. What’s more, bank credit has picked up only slightly so far, growth is still lower than double digits. As the economy picks up steam and credit growth improves, banks will have fewer surplus funds to invest in government securities. Yields will rise further. A high fiscal deficit will exacerbate the problem.

Catch-22

But perhaps the most significant fact is that the Union Budget for 2022-23 is being framed against an international backdrop very different from that of the last decade or so. For the first time in many years, the central banks in the developed economies are being forced to tighten monetary policy. The sea of liquidity on which asset prices floated is in danger of being drained. Who knows what monsters are about to be uncovered? For a global economy addicted to very low interest rates, nobody is certain about what effect it will have not just on overpriced markets, but also on growth in a world tottering under a huge burden of debt. What will it do to the avalanche of private equity and to the cryptocurrencies and non-fungible tokens? Will the central banks be able to pull off the miracle of a soft landing?

That is why the title of Fidelity International’s report on the outlook for next year is ‘Catch 2022’, a play on Joseph Heller’s novel Catch-22. The phrase has come to mean, according to the Oxford Dictionary, ‘a dilemma or difficult circumstance from which there is no escape because of mutually conflicting or dependent conditions.’

What are these mutually conflicting conditions? Fidelity International points to several of the global ones, the most important one being: ‘how to tighten monetary policy and rein in inflation without killing off the recovery.’ And then it adds the punchline, ‘Ultra-low rates are needed to keep the system afloat given debt levels are higher today than during World War Two.’ No wonder the Bank of America survey of fund managers for December found that 42 percent of them believe that ‘hawkish central bank rate hikes’ are the biggest tail risk to markets.

How could this external risk spill over to Indian shores? Well, we are already seeing the impact on asset prices as a firmer dollar leads to funds moving out of emerging markets. More importantly, if the Indian economy continues to gather steam and the current account deficit increases, the Indian rupee is likely to depreciate, particularly when FPI inflows are not strong. And if the central bank tightening and the slowdown in China affects global growth, then our exports could be affected, hitting our growth too.

Risks galore

There are other risks. COVID-19 is far from finished and the Omicron variant is already ravaging Europe. Nor is it certain that Omicron will be the last of the lot—in the Greek alphabet there are still eight letters left if we are to go all the way to Omega. Under the circumstances, strengthening the health sector is a must and government spending on health needs to go up substantially.

Then there are early signs that the climate is already changing, in the shape of more frequent incidents of extreme weather. The government will have to set aside funds to promote investment in green energy.

And then there is defence. With a belligerent China on our doorstep, it won’t do to let our guard down. Nor can it be business as usual---we have to find the money to upgrade our weapons and make use of the latest technology. There can be no cutting corners here.

Finally, here’s what the Monetary Policy Committee said this month: ‘The domestic recovery is gaining traction, but activity is just about catching up with pre-pandemic levels and will have to be assiduously nurtured by conducive policy settings till it takes root and becomes self-sustaining.’ As we can see, not everybody is cheering the V-shaped recovery. There’s a huge informal sector out there that has been badly scarred by the epidemic. Overall demand may still be constrained because of the distress in the informal sector. Some analysts have said that the pandemic has affected India’s potential growth, with the IMF pegging long-term potential growth a comparatively low 6 percent per annum.

That’s where we come to the Catch-22 facing the finance minister. As things stand at present, if the government is able to do some big ticket divestment, it’s very likely that this year’s fiscal deficit target will be met. But here’s what the half-yearly review of the government’s finances in the RBI Bulletin said, ‘Going forward, notwithstanding renewed concerns associated with the new omicron variant of the virus, as economic revival gains further traction, the Centre and States should provide credible medium-term glide paths towards fiscal policy normalisation so that fiscal buffers can be replenished to deal with future economic shocks, if any.’

That’s not the only objective. The higher current account deficit will have to be financed by foreign investment. A high fiscal deficit may therefore not be desirable, particularly in the context of inflationary pressures. Foreign investors would not welcome a depreciating rupee.

Squaring the circle

But if the government has to do all this spending, while also ensure that its debt doesn’t go up, how will it square this circle?

The answer is the same as was given in last year’s path-breaking budget--by privatisation, disinvestment and asset monetisation. Apart from bringing in the moolah, it will also send out several signals. It will burnish the government’s already shiny credentials as one that is carrying out structural reforms. It will set India apart from the ruck of emerging markets, reinforcing its premium over them. It could lead to an inflow of foreign funds at a time when our current account deficit is set to widen and risk appetite among portfolio investors may be low.

But that leads us to another Catch-22---if investor appetite is low, will the government sell off its family silver? Or will it dither and procrastinate, waiting to time the market?

There is another long-discussed policy weapon—including India in the global bond indices. That could lead to inflows into our bond markets, keeping yields low and helping the recovery along. But for that to happen, fiscal consolidation is needed.

In short, the Union Budget for 2022-23 will be made against a backdrop of great uncertainty. The uncertainty is even greater than at the time of the last budget, because the one-point agenda then was to rebound from the ravages of the pandemic. This time, while the pandemic persists, new risks have arisen. The choices the finance minister makes in the budget will tell us how well the Indian economy will navigate these risks.

Discover the latest Business News, Sensex, and Nifty updates. Obtain Personal Finance insights, tax queries, and expert opinions on Moneycontrol or download the Moneycontrol App to stay updated!

Find the best of Al News in one place, specially curated for you every weekend.

Stay on top of the latest tech trends and biggest startup news.